Chinese Architecture – History and Hallmarks of an Enduring Style

Chinese architecture is the expression of a millennia-old architectural style that has shaped construction throughout East Asia. The basic elements of the Chinese traditional building style have remained essentially unaltered since its beginnings in the early imperial period and the most substantial alterations of these Chinese buildings concerned various ornamental features. Architecture in China has also had a significant impact on Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Mongolian architectural styles, as well as some impact on South and Southeast Asian architecture, particularly Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and the Philippines. Chinese structures are distinguished by the incorporation of contained open spaces, bilateral symmetry, a horizontal focus, Feng shui, and allusions to numerous mythological, cosmological, or symbolically significant themes.

An Exploration of Chinese Architecture

Chinese traditional buildings are typically classified by type, spanning from pagodas to opulent palaces. Because of the widespread use of wood, a somewhat perishable medium, and the scarcity of monumental structures constructed of more lasting materials, most of our historical understanding of ancient Chinese architecture originates from surviving small ceramic replicas and written designs and instructions.

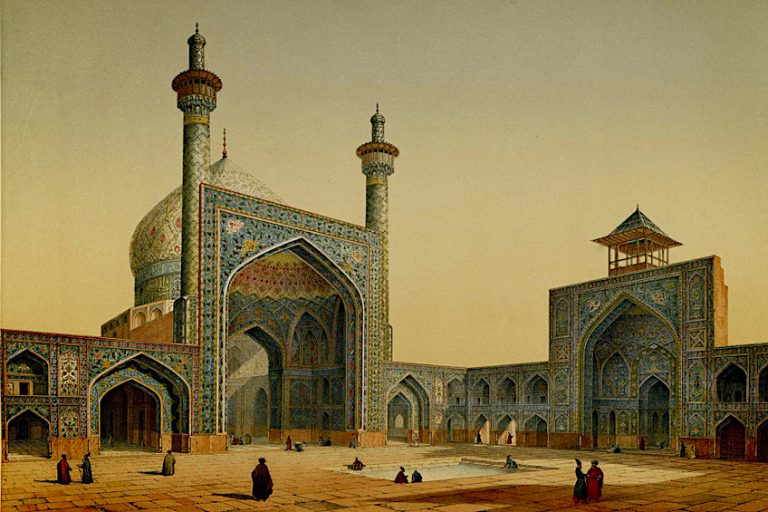

Some Chinese buildings indicate the influences of styles from outside of China, such as the Middle Eastern influence on mosques.

Although there are uniting features, architecture in China differs greatly depending on prestige or function, such as whether the Chinese structures were built for rulers, common folk, or for religious functions.

Features of Chinese Architecture

Vernacular styles connected with distinct geographic locations and ethnic heritages exhibit variations in Chinese traditional buildings.

Chinese architects started to incorporate traditional ancient Chinese architecture into modern architecture during the 20th century, particularly for governmental buildings.

Furthermore, the drive for urban expansion throughout China demands faster construction and a higher floor area ratio: consequently, in urban centers, enthusiasm for Chinese traditional buildings with less than three stories has waned in preference for high-rises. Here is a list of common features found in many Chinese buildings.

Bilateral Symmetry

The focus on alignment and bilateral symmetry in Chinese architecture, which represents equilibrium, is an essential aspect. These may be found everywhere in the architecture of China, from royal complexes to simple ancient Chinese housing. To ensure overall symmetry, secondary components are arranged as wings on each side of the primary structures. Chinese buildings are often designed with an odd number of columns to provide an even set of bays.

Chinese gardens, in contrast to Chinese structures, are asymmetrical.

Gardens are intended to create continuous movement. The classic Chinese garden’s design is founded on the idea of “Man and nature as one,” as opposed to the house, which represents the human sphere existing with but apart from the natural world.

The goal is for people to feel immersed by and at one with nature.

Water and stones are two vital landscape features. Water denotes nothingness and life, while stones symbolize the goal of immortality. The mountain represents yang (fixed beauty), whereas the sea represents yin (dynamism).

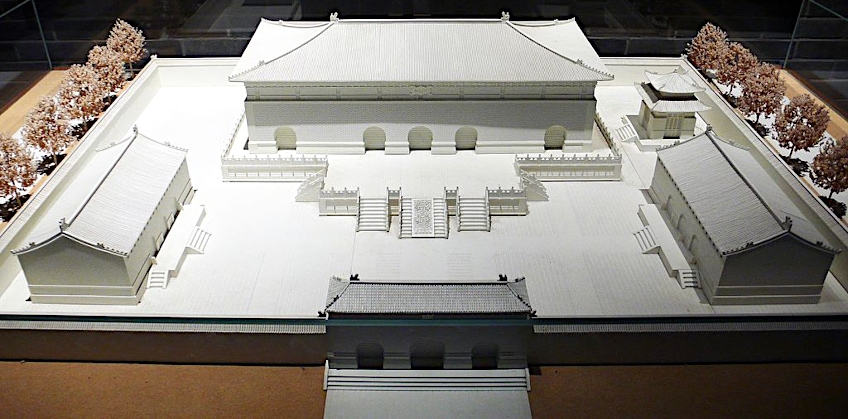

Open-Space Enclosures

Building complexes encircle open areas in most Chinese architecture. Courtyards and sky wells are two types of enclosed areas. Open courtyards are a popular design element in many constructions. This is best seen in Siheyuan, which consists of an empty area encircled by buildings that are connected to each other either directly or via verandas. Although big open courtyards are less prominent in Chinese architecture in the south, the idea of an “open space” enclosed by buildings may be observed in the “sky well,” a southern architectural structure.

This construction is simply a courtyard formed by the junctions of tightly packed buildings, with a small access space to the sky through the roof. These enclosures help with temperature control and ventilation. Northern courtyards are often open and oriented south to maximize the accessibility of the building’s walls and windows to the sunlight while keeping the frigid north winds at bay. Southern sky wells are tiny in size and catch rainfall from rooftops.

These serve the same purpose as the Roman impluvium by limiting the quantity of light that enters the Chinese structures. Sky wells also direct heated air upward, drawing cold air from lower levels and the outside.

Hierarchy

In Chinese traditional buildings, the perceived hierarchy, prominence, and specific building functions are dependent on the precise positioning of buildings within a complex. Buildings with their backs to the street are the least significant. South-facing structures in the back and more secluded locations with more sunshine exposure are held in higher regard and designated for seniors or historical plaques.

Buildings facing west and east are traditionally for younger family members, whereas buildings at the front are normally for domestic servants.

Front-facing structures in the back of estates are utilized for festive ceremonies as well as the placing of historical halls and memorials. Central courtyards and associated buildings are regarded more essential in multi-courtyard systems than peripheral ones, which are often used for servants’ quarters, storerooms, or kitchens.

Horizontal Accentuation

Chinese traditional buildings, particularly those of the affluent, are constructed with a focus on breadth rather than elevation, with an encircled heavy platform and a huge roof that hangs over this foundation, and with vertical walls deemphasized. Structures that were extremely lofty and big were regarded as unattractive and were thus discouraged. Chinese architecture accentuates the aesthetic effect of a building’s breadth, employing sheer scale to generate awe.

This tendency is in contrast to Western architecture, which values elevation and depth. This usually meant that pagodas towered over other structures. The Forbidden City’s palaces and halls have modest ceilings when compared to similar majestic monuments in the West, but their exterior aspect reflects imperial China’s all-encompassing character.

These concepts have made their way into contemporary Western architectural works, such as the work of Jorn Utzon.

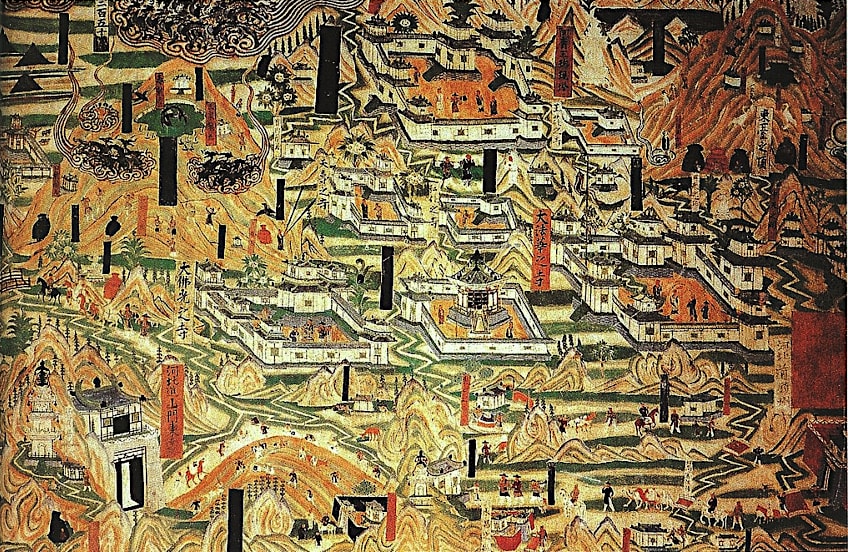

Concepts of Cosmology

Chinese architects planned construction and layout using elements from Chinese cosmological principles such as Taoism and feng shui. It was believed that evil entities moved in straight lines, so the screen walls had to always face the main entrance. The structure has to be designed with its rear to a raised landscape and waterways in front. The building included pools, ponds, wells, and other water sources.

It was necessary to align a structure along a north-south axis, with the structure facing south. The two sides needed to be oriented east and west, respectively.

The employment of specific colors, numerals, and cardinal directions expressed a belief in a sort of immanence, in which the character of an object might be entirely contained inside its own form. Chang’an and Beijing are classic Chinese urban design models that express cosmological notions.

Types of Traditional Chinese Buildings

From ancient Chinese housing to ornate palaces, there are a few distinct styles of architecture in China. The purpose of the buildings, for instance, whether they were erected for ordinary people, royalty, or for religious activities, can influence the forms of Chinese architecture. Let’s take a more in-depth look at each of these styles.

Domestic Architecture

Due to their predominantly wooden structure and inadequate upkeep, ordinary citizens’ dwellings have weathered significantly worse than nobility’s palaces.

Korman asserted that even centuries after the development of the universal design, the ordinary dwellings did not alter much: early 20th-century residences were identical to later and mid-imperial homes.

The heart of the structure was an altar for deities, and it was also used during festivals in these dwellings. On its sides were bedrooms for seniors; on its two wings were bedrooms for younger relatives, in addition to the dining room, living room, and kitchen, however, the living room was occasionally near the center. When extended families grew too large, one or two more sets of “wings” had to be erected.

Traders and officials chose an imposing gate to block off the front. All structures were officially regulated, and the height and length of the building, as well as the building’s colors, were supposed to represent the owner’s status. To protect themselves from thieves, some common people in dangerous areas erected community strongholds known as Tulou. Tulou design, popular among the Hakka in Jiangxi and Fujian, represents the traditional belief in harmony between people and nature. People used local resources to make their walls, which were commonly made of compacted earth.

On the lowest two stories, no windows faced the exterior of the complex, but the inside featured a common courtyard where residents could congregate.

Imperial Residences

Certain architectural aspects were designated for Emperor of China structures. The usage of imperial yellow roof tiles is one example. Most of the structures in the Forbidden City still have yellow tiles on them. Hip roofs with slanted sides could only be used by the emperor. Single-eave and double-eave hip roofs were the two varieties. The Hall of Supreme Harmony is the model for double eaves. Blue roof tiles represent the sky in the Temple of Heaven. Roofs are usually always supported by brackets, an attribute shared exclusively by the greatest religious structures.

The wooden columns and wall surfaces of the structure are typically red. Black is frequently featured in pagodas. The gods were said to be motivated to come to earth by the color black.

Numerology influenced Imperial Architecture, which is why the number nine was used in much of the design and why the Forbidden City in Beijing is supposed to be one room shy of heaven’s famed 10,000 chambers.

The significance of the East in aligning and situating Imperial structures is a sort of sun worship practiced by many ancient societies, representing the ruler’s association with the Sun.

Religious Chinese Structures

In general, Buddhist architecture adheres to the imperial style. A big Buddhist monastery will often include a front hall with sculptures of the Four Heavenly Kings, followed by a vast hall with Buddha statues. Lodgings are available on both sides. Some of the most notable examples are the 18th-century Putuo Zongcheng Temple and Puning Temple. Buddhist monasteries may also contain pagodas, which may store Gautama Buddha relics; early pagodas are generally four-sided, while later pagodas are usually eight-sided. Daoist architecture is typically in the commoners’ style.

The main entrance, on the other hand, is normally on the side, due to belief concerning demons trying to access the buildings.

In contrast to Buddhist temples, the major god in a Daoist temple is positioned in the main hall towards the front, with minor deities in the rear hall and on the edges. This is due to Chinese people’s belief that the spirit lives on after the body dies.

The powers of cosmological yin/yang, the two forces from earth and heaven that generate eternity, are depicted in the Han grave design.

The highest pre-modern structure in China was constructed for both religious and military uses. The Liaodi Pagoda, built in 1055 AD as the Kaiyuan monastery’s crowning pagoda in ancient Dingzhou, was also used as a strategic watchtower for Song dynasty troops to detect anticipated Liao dynasty troop activities.

Notable Examples of Renowned Chinese Structures

Now that we have discussed the features and types of Architecture in China, we can look at a few notable examples. These exemplify the types of Chinese buildings that were previously covered in the section above. These magnificent Chinese structures eloquently exhibit the people’s creative character and traditions.

The Mausoleum of Qin ShiHuang (209 BCE) – Lintong District, China

| Date Completed | 209 BCE |

| Architect | Qin Shihuang (259 BC – 210 BC) |

| Function | Mausoleum |

| Location | Lintong District, China |

The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of China was discovered by chance in 1974 when farmers excavating for a well unearthed six clay warrior sculptures. The archaeological analysis uncovered three massive subterranean chambers (known as “pits”) holding shattered shards of terracotta soldiers as the discoveries were gaining national attention. These life-sized, ceramic figurines represent warriors, with every aspect of their clothing beautifully depicted and remnants of their original paint still visible at the moment of their unearthing.

The terracotta warriors were unlike any tomb figurines ever discovered.

Furthermore, pits one, two, and three were only a minor section of what up constitutes the First Emperor’s huge tomb complex, most of which remains unexplored due to restrictions placed by the Chinese government to protect the site.

The First Emperor began as the Qin state’s ruler. He conquered the nations that occupied much of China’s modern territory with aggressive military operations, thereby bringing an end to the Warring States Period. He consolidated the politically and culturally diverse states into a single, unified governmental entity. Among his major construction initiatives was a gigantic mausoleum of exceptional magnificence, the magnitude, and richness of which became legend with the passage of time.

Nonetheless, none of the incredible legends recorded in the written records readied archaeologists for what they have thus far discovered in the First Emperor’s Mausoleum.

Big Wild Goose Pagoda (648 AD) – Xi’an, China

| Date Completed | 652 AD |

| Architect | Xuanzang (602 – 664 AD) |

| Function | Tomb |

| Location | Xi’an, China |

The multi-story pagoda is a work of art. It was built using layers of bricks rather than cement. The bracket design of traditional Chinese architecture was also utilized in the pagoda’s construction. The gaps between the brick layers of the pagoda are plainly evident. The pagoda’s large body, with its somber look, simple design, and towering construction, is an excellent example of Chinese traditional building style. The Tang Dynasty erected the Pagoda to study Buddhist teachings.

Despite several decades of weather, conflict, and seismic activity that destroyed much of the original materials of the construction, a pagoda of this name and type still stands on the site.

The Tang administration authorized the construction of a room for the translation of Buddhist texts in order to persuade the temple’s then-headmaster, Master Xuanzang, to accept the position. Xuanzang was a Buddhist monk who journeyed to India, interpreted Sanskrit scriptures, and established awareness, karma, and rebirth beliefs that were eventually embraced by several mainstream schools of Buddhism.

The temple used to have 13 courtyards and 1,880 magnificent-looking chambers.

During the Tang Dynasty, it was a massive structure. However, following the dynasty’s collapse, it began to deteriorate steadily. The halls and chambers that have remained until this day were erected during the Ming Dynasty.

The Forbidden City (1420) – Beijing, China

| Date Completed | 1420 |

| Architect | Kuai Xiang (1377 – 1451) |

| Function | Palace complex |

| Location | Beijing, China |

The Forbidden City is a vast precinct in the center of China’s capital, Beijing, with recolored walls and yellow glazed roof tiles. The precinct is a micro-city in its own right, as the name implies. The Forbidden City, which is about a kilometer long, is made up of more than 90 palace compounds, and 98 structures, and is encircled by a moat. For nearly 500 years, the Forbidden City served as China’s governmental and religious center.

During the Qing and Ming dynasties, the Forbidden City housed 24 emperors, their relatives, and domestic servants once it was completed in 1420. Puyi, the final inhabitant, was evicted in 1925 when the area was converted into the Palace Museum.

Despite the fact that it is no longer an imperial precinct, it continues to be one of the most significant cultural heritage locations and the most attended museum in the Republic of China, with an estimated 80,000 visitors daily.

The Temple of Heaven (1420) – Beijing, China

| Date Completed | 1420 |

| Architect | Emperor Shizong (15th century) |

| Function | Temple |

| Location | Beijing, China |

The Temple of Heaven Park is the biggest and most emblematic of China’s ancient ceremonial structures. Initially, the temple was where Ming and Qing rulers performed the Heaven Worship Ceremony. The Temple of Heaven was established in 1420 and was expanded and restored throughout the reigns of Ming Emperor Jiajing and Qing Emperor Qianlong. It was presented to the general public as a park in 1988, displaying ancient history, philosophy, and religion. Its majestic architectural style and significant cultural significance provide insight into old Eastern civilization practices.

As the “Sons of Heaven”, Chinese emperors were forbidden from constructing a palace for themselves that was larger than the earthly residence devoted to Heaven, hence the disparity in total size between the two complexes. A large wall surrounds the temple. The northern section of the wall is semicircular, representing the skies, while the southern part is square, representing the earth. The northern section is higher than the southern section.

This design depicts the heavens as high and the world as low, and it reflects an ancient Chinese belief that “the earth is square and heaven is round.”

Shenyang Imperial Palace (1625) – Shenyang, China

| Date Completed | 1625 |

| Architect | Nurhaci (1559 – 1626) |

| Function | Palace |

| Location | Shenyang, China |

The Shenyang Imperial Palace, is a cultural treasure in great condition. Nurhaci started developing the palace in 1625, and it was finished in 1636 under Abahai’s rule. It was then enlarged under the reigns of Qianlong and Jiaqing. There are eight gates and it takes around 332 paces to go around the palace.

The city’s streets formed the symbol of a hashtag, or “#”.

In the early Qing Dynasty, the royal palace was built in the middle of the hashtag form. After the Qing Army conquered the Shanghai Pass, the residence was designated the Fengtian Xinggong as opposed to the previous name of the Imperial Palace of Shengjing.

The Palace contains around 90 structures containing 300 rooms and residences. It is highly adorned and dazzlingly magnificent, surrounded by high red walls and coated with golden tiles on the hall ceiling.

There are no embellishments on the ceiling, and only motifs of blue landscapes and white clouds are adorned on the roof boards, giving the hall a high and exquisite appearance. Colored murals portraying dragons in the skies, and other subjects may be seen on the beams and rafters. A staircase was created in the center of the hall. A sinuous golden dragon in a realistic pose is located in front of the staircase. During Qianlong’s rule, the folding screen, sundial, throne, measuring instrument, and other artifacts were displayed.

Nanshan Temple (1988) – Sanya, China

| Date Completed | 1988 |

| Architect | Chen Yong (1963 – Present) |

| Function | Temple |

| Location | Sanya, China |

Nanshan Temple stands out against the backdrop of the ocean and mountains, and it is considered an auspicious location for Buddhism. The Sea Watch Terrace and the Golden Jade Guanyin Statue are two further highlights of the shrine.

Nanshan Temple is well-known for housing the world’s largest Guanyin Bodhisattva.

The temple’s structures, with red roofs, enormous halls, and white walls, perfectly exhibit aspects of ancient Chinese architecture. The zone has been classified as a Chinese Tourism Development Prioritized Project and will be further developed.

The Chinese government has specifically designated Hainan as the sole province in China for the growth of tourism as a core economy. It is also planned to serve as a testing ground for China’s tourism reforms and technological innovation. The Nanshan Temple complex is a large park with multiple temples located all across the terrain and linked by various pedestrian routes. The complex’s primary entry is through a gate designed in the manner of Chinese traditional building methods from the 5th and 6th centuries.

There are various Buddhist monuments and buildings along the walk, as well as tiny businesses offering religious items, incense, and vegetarian cuisine.

Urban Planning

Urban planning in China is founded on geomancy and the well-field land partition system, both of which have been employed since the Neolithic period.

The design of Hongcun city in Anhui during the Southern Song dynasty was focused on “equilibrium between man and environment,” with the city oriented to the south and encircled by mountains and water.

It is a meticulously built old village that demonstrates the nature and human intergraded environmental design idea, based on feng shui. Because battles were common in northern China, many residents relocated to southern China. The courtyard home construction method was adopted in southern China. Tangyuan is a great example of a planned town that incorporates feng shui aspects.

Construction

Traditionally, wood was used as a key construction material. Furthermore, Chinese culture believes that life is intertwined with creation and that humans should engage with living things. Stone was connected with the houses of the dead. Wooden constructions, on the other hand, are less durable than other building materials.

The Songyue Pagoda is China’s oldest surviving pagoda; its use of brick rather than wood enabled it to endure for centuries.

Stone and brick construction progressively gained popularity after the Tang period. The first evidence of this change may be seen in construction projects like the Zhaozhou Bridge, which was finished in 605 AD, and the Xumi Pagoda, which was erected in 636 AD.

Some brick and stone construction were utilized in earlier dynasties’ subterranean tomb construction. There were no known completely wood-constructed Tang Dynasty structures in the early 20th century; the earliest so far identified was the 1931 discovery of the Guanyin Pavilion at Dule Monastery, dated to 984 AD. Compacted soil was used to build the first walls and platforms.

Although the stone and brick Great Wall as seen today is a Ming-era reconstruction, ancient parts of the Great Wall of China employed stone and brick.

Buildings for the general public and the elite were often made of soil mixed with stones or bricks on high platforms that enabled them to endure. This type of architecture was first seen during the Shang period.

Structure

Raised platforms are commonly used as foundations for most constructions. Vertical support beams may be braced by stone pedestals that are occasionally supported by piles. Platforms in lower-class buildings are made of compacted earth and paved with ceramics or bricks. Vertical support beams are pushed into the ground in the most basic circumstances. Upper-class buildings are usually built on elevated stone-paved compacted earth or stone platforms with intricately carved massive stone plinths to hold enormous vertical construction beams. The beams are held in place by resistance and the load of the structure.

The roof is supported by large structural timbers. Load-bearing pillars and beams are often made of huge trimmed logs. These beams are either directly joined or, in bigger and higher-class constructions, coupled together via brackets. In finished constructions, these structural timbers are clearly seen. It is unknown how the ancient builders hoisted the columns into place.

Timber frames are often constructed using joinery, rather than glue or nails. These semi-rigid structural connections enable the timber structure to withstand twisting and torsion under extreme compression.

The installation of strong beams and roofing improves structural stability. The absence of nails or glue, the utilization of non-rigid supports, as well as the utilization of wood as structural components, allow structures to slide, bend, and hinge while absorbing seismic stress, vibrations, and ground shifting without substantial damage. Ordinary individuals utilized artwork to convey their respect for the house.

Chinese architects were inspired by concepts from Buddhism, but the structures of ancient China remained surprisingly consistent in essential appearance over the ages, influencing much of the architecture of neighboring East Asian kingdoms, particularly ancient Korea and Japan. Regrettably, few ancient Chinese structures have survived to the present day, but reconstructions may be created using clay models, descriptions in historical writings, and portrayals in art such as wall murals and engraved metal objects.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Characterizes Chinese Architecture?

Chinese architecture is incredibly consistent. Elevated pavilions, fortified compounds, timber panels and columns, beautifully landscaped gardens, yellow glazed roof tiles, meticulous town planning, and the utilization of space are all significant features of ancient Chinese architecture, many of which are still playing a significant role in modern architecture throughout East Asia. The most common type of construction, at least for major structures for public or aristocratic usage such as halls, temples, and gate towers, was erected on a raised platform of compacted earth and covered with stone or brick.

What Are the Types of Chinese Traditional Buildings?

There are several architectural styles in China, ranging from ancient Chinese houses to magnificent palaces. The purpose of the structures, such as whether they were built for regular people, monarchy, or religious purposes, can have an impact on the styles of Chinese architecture. These styles include those of ordinary civilian housing, imperial residents, and religious Chinese structures.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Chinese Architecture – History and Hallmarks of an Enduring Style.” Art in Context. January 16, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/chinese-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 16 January). Chinese Architecture – History and Hallmarks of an Enduring Style. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/chinese-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Chinese Architecture – History and Hallmarks of an Enduring Style.” Art in Context, January 16, 2023. https://artincontext.org/chinese-architecture/.