Aztec Art – Masterpieces of the Culhua-Mexica People

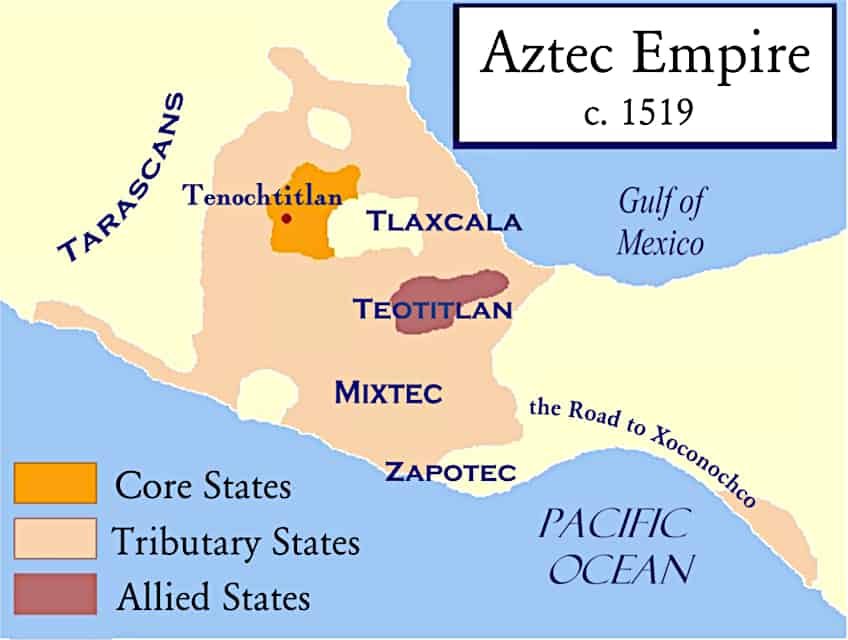

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Aztec civilization, located in the city of Tenochtitlan, ruled most of Mesoamerica. As the culture expanded, the Aztecs’ art and architecture spread, assisting the Aztec empire in achieving political and cultural hegemonic power over these regions and leaving a record of the Aztec artistic talents for posterity. From huge stone Aztec sculptures to tiny, exquisite Aztec carvings of insects, and ancient Aztec paintings, the Aztec empire developed a wide variety of notable Aztec artworks. From Aztec ancient artworks to modern-day Aztec art drawings inspired by a bygone era, let’s take a deeper look at the Aztecs’ art and architecture.

An Exploration of Aztec Artwork

The Aztecs created handcrafted ceramics, beautiful silver and gold jewelry, and magnificent featherwork costumes. The Aztecs were deeply committed to both art and religion, and the two were inextricably linked. Our understanding of the Aztec empire and culture is mostly based on pictorial codices and Aztec ancient art. Aztec artists included images of their deities in much of their Aztec artworks. Much of the gold and silver jewelry was lost to the invading Spanish, who melted it down for coins.

Regrettably, feather works do not stay forever, however, some samples persist. Time also destroys textiles, and ceramics are brittle. Nevertheless, the Aztecs’ sculptures survive to demonstrate the Aztecs’ amazing creativity.

While many of the Aztec populace worked in agriculture to feed the Aztec empire and others were active in the extensive commercial networks, many others spent their time creating the artworks that the aristocratic Aztecs admired. Thus, examples of creative ingenuity in precious metal jewelry embellished with obsidian, Jade, turquoise, greenstone, and coral may still be seen, primarily in tiny items such as earrings.

Influences on Aztec Artwork

Common themes flow across Mesoamerican society’s history, notably in art. The Olmec, Toltec, Maya, and Zapotec civilizations, among others, continued an artistic legacy that included large stone sculptures, imposing architectural features, adorned ceramics, patterned stamps for textile and skin art, and spectacular metalworks, all of which were used to portray animals, people, plants, divine beings, and characteristics of religious ceremony, particularly those ritual practices and gods associated with reproduction and agriculture.

Aztec artisans were also inspired by their counterparts from neighboring states, particularly artists from Oaxaca and the Gulf Coast’s Huastec area, which had a rich heritage of three-dimensional sculpting. These numerous influences, along with the Aztecs’ broad tastes and love for old art, resulted in one of the most diversified ancient cultures worldwide.

Sculptures depicting the grace and beauty of the human and animal form might have originated from the same studio as terrible gods with abstract images.

Types of Aztec Artworks

The skills and superb workmanship of the Toltecs, who predate the Aztecs in central Mexico, were immensely valued by the Aztecs. The Aztecs regarded Toltec products as the pinnacle of art. Here are a few of the most prominent types of Aztec artwork.

Aztec Metalwork

Metalwork was a specialty of the Aztecs. Albrecht Durer, a prominent Renaissance artist, viewed some of the artifacts brought back to Europe and said, “I have never witnessed in all my days something which so thrilled my heart, as these things. I observed beautiful creative artifacts among them, and I marveled at the delicate cleverness of the folks in these faraway nations”.

Unfortunately, these pieces, like most other artifacts, were smelted for currency, thus relatively few specimens of the Aztecs’ superb metalworking talents in silver and gold exist.

Smaller artifacts, such as gold lip labrets, rings, pendants, earrings, and necklaces in gold depicting anything from tortoise shells to deities, to eagles, have been uncovered, attesting to the lost-wax casting and filigree workmanship of the greatest artisans.

Aztec Sculptures

The Aztecs’ sculptures fared better, and their subjects were frequently persons from the vast pantheon of deities they worshiped. These Aztec carvings, made of wood and stone and often colossal in scale, were not idols housing the spirit of the god, since the energy of a specific deity was supposed to live in holy bundles preserved within temples and shrines in Aztec religion.

Yet, it was deemed necessary to “fuel” the Aztecs’ sacred sculptures with blood and costly goods, which is why tales from the conquistadors of massive monuments covered in blood and adorned with gems and gold circulated.

Other big circular sculptures include the superb sitting deity Xochipilli and the many reclining figures with a depression cut in the chest used as a container for the organs of sacrificed people.

These would have been painted in a variety of vibrant colors in the past. Smaller-scale sculptures have been discovered at several locations around Central Mexico. These are frequently local deities, particularly gods associated with agriculture. The maize goddess Xipe Totec and upright female images of a maize deity, generally with an elaborate headdress, are the most prevalent. These sculptures and related clay figurines, while lacking the elegance of imperial-sponsored art, frequently portray the more beneficent aspect of the Aztec gods.

Miniature Aztec carvings were also popular, with subjects like flora, insects, and shells reproduced with expensive materials, including pearl, rock crystal, amethyst, obsidian, shell, and – perhaps the most valuable of all materials for the Aztecs – jade.

Aztec Ceramics

The Aztecs produced a wide range of ceramics. Orange wares, which are orange-burnished earthenware with no slip, were popular. Ceramics having a reddish slip are known as red wares. Polychrome pottery is defined as pottery with an orange or white slip and painted patterns in red, orange, brown, and black. “Black on orange”, which is orange porcelain embellished with black-painted motifs, is quite prevalent.

Clay griddles for preparing food, plates, and bowls for dining, pots for meal preparation, mortar-type containers with slit bases for crushing chili, and various types of tripods, dishes, and goblets were common daily vessels. Vessels were baked at low temperatures in basic kilns.

Polychrome pottery was transported from the Cholula region and was highly valued as a luxury item, although the indigenous black-on-orange patterns were also used on a daily basis.

Ancient Aztec Paintings and Aztec Art Drawings

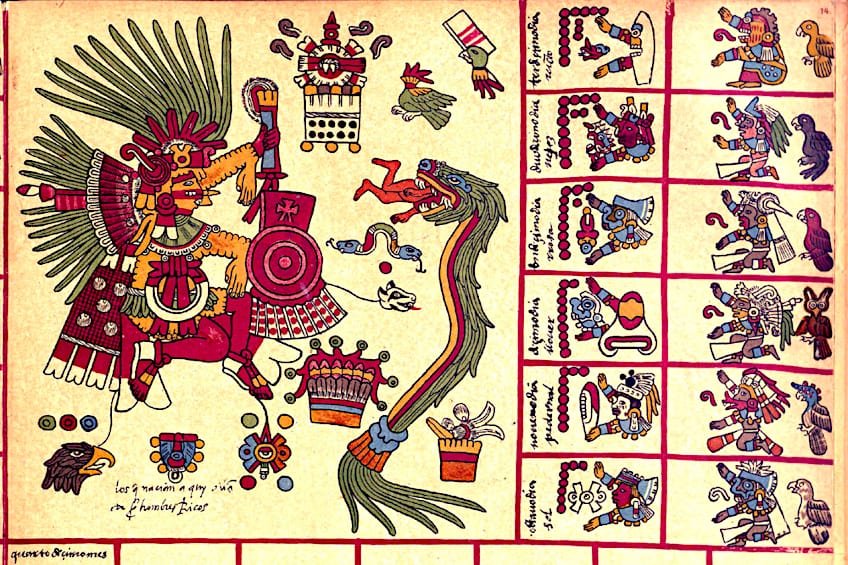

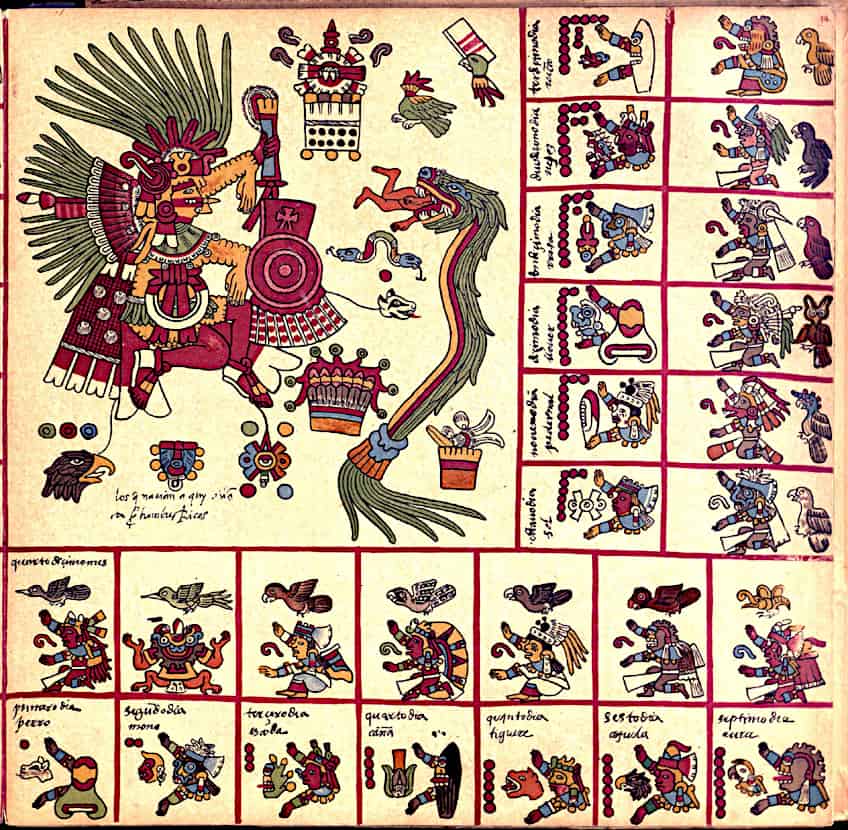

Aztec art drawings and paintings were created on animal skin, cotton, and paper made from bark, as well as pottery and stone and wood carvings. To make the pictures turn out more clearly, the surface of the material was frequently first coated with gesso. Paintings and writing were recognized by the words“in tlilli, in tlapalli”, which means “black ink, red pigment”. There is only a handful of surviving painted Aztec books. None of these are definitively shown to have been made before the invasion, although some codices must have been produced either just before or shortly after the conquest – before the customs for making them were greatly disrupted.

Even if certain codices were created after the conquest, there are grounds to believe that they were copied from pre-Columbian originals by scribes. Some believe the Codex Borbonicus to be the sole existing Aztec codex created before the invasion; it is a calendric codex that describes the day and month counts while designating the patron deities of the various time periods.

Others believe it has aesthetic characteristics indicating post-conquest construction. Some codices were produced post-conquest, occasionally commissioned by the colonial administration, such as Codex Mendoza, and were adorned by Aztec creators while under the regulation of Spanish officials, who also occasionally commissioned codices characterizing precolonial religious processes, such as Codex Ros.

Following the conquest, the clergy sought and burned codices containing religious material, although other sorts of painted books, mainly historical tales and tax lists, continued to be created. Although portraying Aztec deities and discussing religious activities shared by the Aztecs of the Valley of Mexico, the codices made in Southern Puebla near Cholula are not always regarded as Aztec codices because they were created outside of the Aztec “heartland”. Teotihuacan produced the earliest ancient Aztec paintings.

Templo Mayor is home to the majority of our present Aztec murals. The Aztec capital was lavishly embellished with paintings. Humans are shown in Aztec paintings in the same way as they are in the codices. One fresco found in Tlatelolco portrays an elderly man and lady. This might be the gods Oxomico and Cipactonal.

Aztec Featherwork

Featherwork, the fabrication of elaborate and brilliant mosaics of feathers and their usage in clothes as well as ornamentation on weaponry, battle banners, and warrior outfits, was a particularly esteemed art form among the Aztecs. The Amanteca were a class of highly talented and revered artisans who manufactured feather things, named after the Amantla area of Tenochtitlan where they worked and lived. They were not obligated to pay taxes or conduct public duty. The Florentine Codex describes how feather crafts were manufactured. The Amanteca created their artwork in two ways. One was to use agave string to bind the feathers in place for three-dimensional devices such as fly whisks, fans, bangles, headgear, and other items. The second and more challenging technique was a mosaic technique known as “feather painting” in Spanish. These were mostly done on feather cloaks and shields for idols.

Feather mosaics were arrangements of minute pieces of feathers from a broad variety of birds, often produced on a paper foundation composed of cotton and paste, then backed with amate paper, although other types of paper and direct on amate were also used.

Layers of “ordinary” feathers, colored feathers, and expensive feathers were used in these creations. First, a model was created using poorer-quality feathers and priceless feathers only found on the top layer. Orchid bulbs were used to make the glue for feathers during the Mesoamerican era. Feathers from both local and distant sources were utilized, particularly in the Aztec Empire. The feathers were collected from both wild and farmed birds, with the best quetzal feathers originating from Guatemala, Chiapas, and Honduras. Taxes and trade were used to purchase these feathers.

Fewer than 10 pieces of genuine Aztec featherwork survive today due to the difficulties of preserving feathers.

Aztec Artwork as Propaganda

The Aztecs, like their cultural forefathers, used art to strengthen their militaristic and cultural superiority. Imposing structures, frescoes, sculptures, and even manuscripts, particularly at significant locations like Tenochtitlan, not only reflected and even recreated fundamental components of Aztec religion, but they also informed subjected peoples of the riches and power that allowed their creation and fabrication.

Temples

The Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan, which was much more than a massive pyramid, was the ultimate instance of art being used to transmit governmental and religious ideas. It was meticulously sculpted to resemble the holy serpent mountain of the earth Coatepec, which is central to Aztec mythology and religion. Coatlicue (which to the Aztecs represented the earth) delivered her son Huitzilopochtli (the Aztec manifestation of the sun), who overcame the other gods (believed to be the stars) commanded by his sister Coyolxauhqui (the Aztec manifestation of the moon). On top of the pyramid, a shrine to Huitzilopochtli and another to the rain deity Tlaloc were constructed. The serpent sculptures along the pyramid’s base, as well as the Great Coyolxauhqui Stone, carved about 1473 and located near the pyramid’s foot, show the severed corpse of the fallen goddess in relief.

The stone, like earlier sculptures such as the Tizoc Stone, linked cosmic imagery to the contemporaneous conquest of local adversaries. The defeat of the Tlatelolco is mentioned in the case of the Coyolxauhqui Stone.

Finally, when the inside of the Templo Mayor was investigated, a large trove of sculptures and artistic artifacts was found entombed with the corpses of the deceased, and some of these pieces are artworks that the Aztecs had obtained from more ancient civilizations. Temples praising the Aztec worldview were also built in conquered regions.

The Aztecs usually maintained established administrative and political frameworks, but they did implement their own divinities in a hierarchical system above local divinities, primarily through Aztec art and architecture, backed up by sacrificial festivities at these unique sacred sites, which were typically built on preceding sacred sites and frequently in stunning environments such as on mountain peaks.

Aztec Empire Imagery

Many lesser-known deities than Huitzilopochtli are represented in Aztec art, as are a considerable number of representations of environment and agricultural deities. The works of art of the river goddess Chalchiuhtlicue in ancient Tula are among the most renowned.

These and other Aztec artworks were often created by local artisans and may have been sponsored by state officials or individual colonists from the Aztec capital.

Architectural artwork, rock engravings of deities, beasts, and shields, as well as other art pieces, have been discovered from Veracruz to Puebla, particularly around hills, towns, springs, and caves. Furthermore, these creations are frequently one-of-a-kind, implying the lack of any organized workshops.

Notable Examples of Aztec Artwork

Many Aztec families and even communities dedicated themselves to creating artwork for Aztec elites. Each art form has its own guild. The guild nobility supplied the raw materials, while the artists produced the final works—the spectacular stone carvings, jewels, complex ceremonial outfits for large religious events, and feather cloaks, shirts, and headdresses.

The Aztec rulers received art pieces as tribute, or the painters sold them at Tlatelolco’s enormous marketplace.

Despite the fact that most Aztec artworks were destroyed after the Spanish invasion, many superb examples of each individual art genre exist to demonstrate to visitors the extraordinary ability and technique of Aztec artisans. Here are a few notable examples of Aztec artworks.

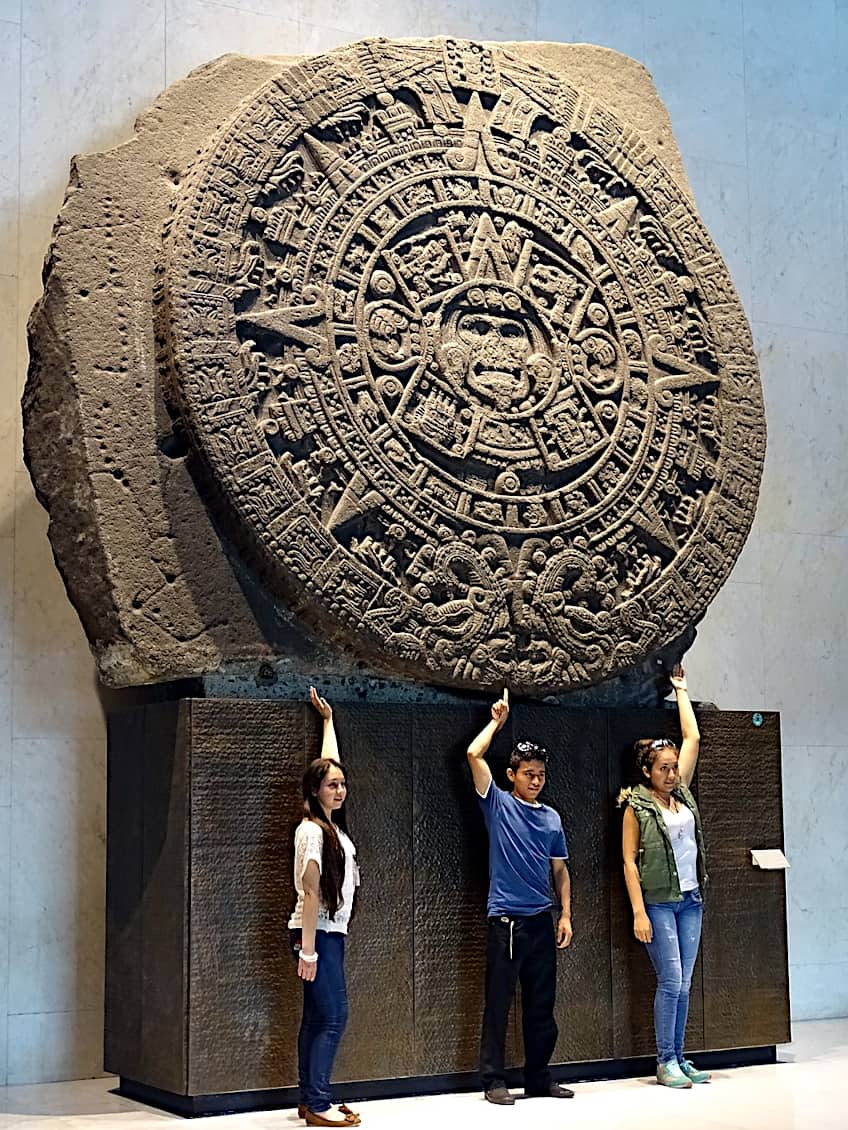

The Aztec Calendar (c. 1427)

| Artist | Unknown Aztec artist (c. 1427) |

| Created | c. 1427 |

| Medium | Stone |

| Location | National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico |

The Aztec Calendar is undoubtedly the most recognizable art piece created by any of Mesoamerica’s great civilizations. The stone, found in the 18th century near Mexico City’s cathedral, was etched about 1427 and depicts a solar disk with the five sequential realms of the sun from Aztec tradition. The basalt stone measures 3.78 meters in diameter and about a meter wide, and it was formerly part of Tenochtitlan’s Templo Mayor complex.

The stone’s center has an image of either Tonatiuh or Yohualtonatiuh or the primal earth creature Tlaltecuhtli, the latter marking the world’s final devastation when the 5th sun fell to Ground.

The four suns were sequentially replaced around the center face at four points when the gods Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl fought for control of the universe until the age of the fifth sun was reached. The earthly world is represented by two jaguar heads or paws on either side of the center face. The two heads at the bottom center depict fire serpents, and their bodies wrap around the artifact, each culminating in a tail.

The four cardinal directions are also denoted by bigger and smaller points. Originally, it would have been put flat on the ground and probably sanctified with sacrifices. It was discovered flat and upside down, maybe in an attempt to avoid the last cataclysm.

The area immediately surrounding the sun is divided into the 20 Aztec names for each day. Then there’s a beautiful ring encircled by another ring with symbols representing jade and turquoise, solstices and equinoxes, and heaven’s colors.

Coatlicue Statue (c. 1439)

| Artist | Unknown Aztec artist (c. 1439) |

| Created | c. 1439 |

| Medium | Andesite |

| Location | National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico |

Following the invasion of Tenochtitlan by the Spanish in 1521, the Spanish conquerors ordered the methodical demolition of the city, including Mexica monuments and structures. Because the people were instructed to demolish it, they rather submerged it below the water table to spare it from destruction. On the 13th of August 1790, during the excavation of a water channel in Mexico City’s main plaza in front of the National Palace, the Coatlicue monument was originally unearthed. The sunstone was discovered around 100 feet distant a few months later, on the 17th of December 1790.

The unearthing of these two sculptures, together with the uncovering of the Tizoc Stone in 1791, ushered in a new era of Templo Mayor research as modern researchers sought to analyze their intricate symbolism and decode their meanings.

Coatlicue’s huge basalt figure is widely regarded as one of the best specimens of Aztec sculpture. With twin snakeheads, clawed hands and feet, a collar of dismembered hands and hearts, and a garment of squirming snakes – the goddess is scary. The 3.5-meter-high statue, maybe one of four, leans somewhat forward, suggesting the reveal of feminine strength and fear.

The entire dramatic impact of the artwork is so evocative that it is obvious why the figure was re-buried multiple times following its first excavation in 1790. The Coatlicue monument is presently housed in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology.

Stone of Tizoc (c. 1480s)

| Artist | Unknown Aztec artist (c. 1480s) |

| Created | c. 1480s |

| Medium | Basalt |

| Location | National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico |

Tizoc’s enormous round stone is a remarkable blend of cosmic myth and politics. It was initially used as a platform for human sacrifice, and because the captives were generally defeated soldiers, the reliefs around the stone portray the Aztec monarch Tizoc defeating warriors from the Matlatzinca, a territory acquired by Tizoc in the late 15th century CE. The defeated men are also depicted as landless barbarians, whereas the victorious wear the renowned old Toltec aristocratic clothing. The upper surface of the 2.67-meter-diameter stone portrays a sun disk with eight points.

The stone’s lateral side portrays 15 distinct images of a costumed warrior having their hair snatched by another warrior. The first figure, likely the warrior with the greatest headdress, is designated by the Tizoc symbol and wears the symbol of the deity Huitzilopotchli, the adored god of battle.

The warrior being captured has an identifiable geographical glyph in each image. Each of the warriors clutching the other is identifiable by the “smoking foot” motif as well as the smoking mirror emblem in their headpiece, all of which are associated with the god Tezcatlipoca.

The name of the location which had been captured is shown using Aztec glyphs over each conquered soldier. Toponyms are written using a combination of syllabic and logographic characters. The top rim of the stone likewise represents stars, emphasizing the skies, while the symbols at the bottom border represent the earth. When combined with the sun symbolism on top, this connects Aztec conquest and control to the divine.

The Aztecs ruled much of central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries, when they were defeated by Spanish conquistadors. Yet, understanding the Aztec Empire requires first understanding their relationships to other Mesoamerican peoples who came before them, as well as the impact these individuals had on the Aztec empire. One of the most visible links between the Aztecs and the other Mesoamerican cultures may be seen in art. The Aztec Empire is notable for many things, including the wonderful art and creative products made by the Aztecs. Aztec ancient art was greatly inspired by the Aztec people’s religious and cultural rituals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Aztec Art Connected to the Toltecs?

The Aztecs saw themselves as the descendants of the ancient Toltecs. Indeed, the Aztecs revered the Toltecs in a variety of ways, including architecture, art, craftsmanship, and culture. Some scholars have questioned whether the Aztecs descended from the previous Toltec culture, although this has also been suggested regarding other earlier Mesoamerican cultures, like the Teotihuacan. Nevertheless, the Toltec language was Nahuatl, which was also the Aztec language. In addition, the Nahuatl name for Toltec evolved to refer to an artisan in Aztec civilization, referring to their belief that the Toltecs were the pinnacle of Mesoamerican art, culture, and design.

What Was Aztec Art Used For?

Aztec art may be seen in many of the artifacts and buildings utilized by the Aztecs on a daily basis. Aztec pottery, clothing, jewelry, temples, and weaponry, for example, included creative art designs. The Aztecs, in particular, were known to utilize vibrant colors and expressive artwork to portray their culture and religion on these things. Feathers, shells, silver, gold, glass beads, and other gemstones were commonly utilized to manufacture these things.

Was Religion Important in Aztec Artwork?

Aztec art was heavily influenced by religion and deities. As a result, most of the remaining Aztec artwork is based on various Aztec gods. The Tlaloc Vessel, for example, is a ceramic jug unearthed amid the remains of Tenochtitlan’s Templo Mayor. Historians think the pot was made in about 1470. It has a representation of the Aztec god Tlaloc. Tlaloc was a significant deity in the Aztec religion. He was worshiped by the Aztecs as the deity of fertility, rain, and water. He was a prominent deity throughout the Aztec Empire and was generally regarded as a life-giver.

Who Created Aztec Art?

While a large majority of the Aztecs labored in the fields to feed the Aztec empire, and others were active in the extensive trading routes, there were also those that spent their time creating the artworks that the aristocratic Aztecs admired. Therefore, we find creative ingenuity in precious metal jewelry embellished with all kinds of beautiful adornments such as obsidian, jade, turquoise, and greenstone. Pottery from Tenochtitlan and adjacent areas still reveals the Aztecs’ superb abstract iconography. Feather craftsmen created beautifully designed headdresses and shields for the ruler and nobility.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Aztec Art – Masterpieces of the Culhua-Mexica People.” Art in Context. June 5, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/aztec-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 5 June). Aztec Art – Masterpieces of the Culhua-Mexica People. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/aztec-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Aztec Art – Masterpieces of the Culhua-Mexica People.” Art in Context, June 5, 2023. https://artincontext.org/aztec-art/.