Pre-Columbian Art – The History of Pre-Columbian Artifacts

Pre-Columbian art encompasses the visual arts traditions of the native peoples of North, South, and Central America, as well as the Caribbean, from approximately 13,000 BCE to the start of European invasions in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. In many regions, the Pre-Columbian era persisted or experienced a transitional period following these invasions. Various kinds of perishable Pre-Columbian artifacts, like woven textiles, have not survived, although examples of Pre-Columbian ceramics, monumental sculpture, pottery, metalwork in gold, as well as paintings on walls and rocks have endured more frequently. In this article, we shall be exploring the history of Pre-Columbian art, and finding out what makes this period in American history so distinct and important.

The History of Pre-Columbian Art

The first Pre-Columbian artworks to become widely recognized in modern times originated from the Inca and Aztec empires prospering during the era of European invasion, part of which was transported back to Europe unbroken. Increasingly, art from previously fallen civilizations, particularly Maya and Olmec artwork, grew in popularity, most notably for their massive stone sculptures. Because many Pre-Columbian societies lacked any sort of writing system, the visual arts represented their value systems, religion, cosmologies, and philosophy while also functioning as mnemonic devices.

Craftsmen in the Ancient Americas used a variety of materials, including gold, obsidian, and Spondylus shells, to create Pre-Columbian artifacts that conveyed the meanings associated with the materials. These societies typically assigned value to artworks based on their physical properties instead of their imagery, emphasizing their tactile aspects, craftsmanship, and scarcity of materials.

Historical Significance and Origins

Pre-Columbian Visual art was particularly concerned with how humanity fits into the natural and metaphysical realms, our role in the machinations of the cosmos, and ancestral histories. Pre-Columbian art was used for keeping records, calculating, trading, and correspondence. While the term “Pre-Columbian” is typically used to refer to the entire region encompassing all of the Americas and affiliated islands, the primary focus of the history of the visual arts of this period is centered on Central and South America, as well as Mesoamerica.

Inuit and Native North American art usually represented in separate categories.

Central America and Mesoamerica

The Olmec civilization, which existed in Central America from 1200 to 400 BCE, was regarded as the first great civilization. They dwelt in the tropical jungle-like climate of South Central Mexico and were renowned for their exceptionally huge boulder-sculpted heads over 2.5 meters tall. They sculpted in Jade as well, typically focusing on baby figurines as well as fish, animal, and bird carvings. The Olmec heads likewise display very baby-like features, despite the fact that they are representations of mature men, typically in military attire. The Olmec were also the first people in Central America to construct pyramids and ceremonial structures. The Mayans were the next great civilization, primarily an agrarian culture that flourished between 200 and 900 CE. They created petroglyphs and paintings, as well as sculptures and carvings in both rock and wood. The Mayans created one of the most precise calendars that humanity had ever seen, recording time in advance by nearly 10 centuries. Their calendars are intricately designed with hieroglyphics and images.

The Mayan wall murals were as vibrant, unique, and well-rendered as, if not better than, Mediterranean and European art of the same era and kind. The Toltecs were a warring society devoted to merciless gods such as Quetzalcoatl, who expected adoration and sacrifices. The Toltecs are largely recognized for the massive standing statues that defend their ceremonial structures, in addition to their incredible relief sculptures. The Mixtec lived prior to and following the Aztecs, and they were subservient to them while the Aztecs prospered. They created paintings with brightly colored flatly drawn figures. A family tree created using figures instead of text is one example of the kind of art they made. The Aztec empire was one of the most formidable in all of the Americas. They were also incredibly competent mosaic artisans who incorporated their mosaics into their architectural designs as well as ceremonial masks.

South America

The Chavin Civilization of Peru’s Andes highlands were sculptors, potters, and carvers who flourished between 1000 and 300 BCE. Their themes typically feature anthropomorphic beings with human-shaped bodies yet with certain animal traits. Reptiles, birds, and huge cats, most notably the Jaguar, were significant to the Chavin. They were also excellent muralists, as demonstrated by the Chavin de Huantar site. The Nazca River Valley inhabitants are famous for the lines that crisscross through the desert in the form of birds and other intriguing creatures, but this does not constitute the only art created by this civilization.

They were exceptionally innovative in the design and ornamentation of their polychrome Pre-Columbian ceramics, typically incorporating both animal and human forms, but also occasionally featuring abstractions.

The Moche people from Peru’s northern river basins were the finest artists of the entire pre-Columbian world. Their artwork was very life-like and well-crafted. They are well-known for portrait vases with intricately sculpted and skillfully rendered heads. Historians think that the Moche people attributed spiritual value to their Pre-Columbian ceramics and expressed spiritual beliefs through them. Their Art themes ranged from elements of nature and wildlife to philosophical themes such as deities, evil spirits, and sex.

The Wari Empire of the Andes were also skilled ceramicists, particularly in the creation of Pre-Columbian artifacts honoring the Staff God, the first deity to be graphically documented in the Americas. He is usually depicted with a staff in either hand. The Wari were extremely skilled in sculpture and architecture, particularly in stone. The Staff God is encircled by religious emblems at the Gate of the Sun. Portraits in gold and silver were made by the goldsmiths of the Chimu Dynasty on Peru’s coast. They also built on Sican, an earlier Pre-Columbian ceramics art form. Their architectural skills are evident at the Chan Chan Palace. The Chimu tribe also developed a featherwork art form, in which complex headdresses symbolizing air and water creatures were produced.

Notable Pre-Columbian Artifacts

Now that we know a bit more about the various civilizations that arose throughout the history of Pre-Columbian America, we can take a look at a few notable examples of Pre-Columbian artifacts. The ancient Aztec, Maya, and Inca civilizations all created magnificent architectural marvels such as temples, pyramids, and palaces. Sculptures were made by Pre-Columbian artisans in a variety of materials, and the giant Olmec heads and the Aztec Calendar Stone are two of the most well-known Pre-Columbian artworks. Several pre-Columbian civilizations valued pottery as a form of art, and artisans developed a broad variety of forms and styles.

Weaving was another essential form of craftsmanship for many pre-Columbian societies, and textiles were typically highly valued. Certain pre-Columbian cultures used natural colors to create beautiful mosaics and paintings.

Lanzón (c. 500 BCE) in Chavin de Huantar, Peru

| Date Made | c. 500 BCE |

| Civilization | Chavin |

| Type | Stela |

| Medium | Granite |

| Location | Chavin de Huantar, Peru |

The Lanzón is a stela made from granite connected to the Chavin civilization. It is housed at the Old Temple of Chavin de Huantar, which is located in Peru’s central highlands. The Chavin religion, which flourished sometime between 900 and 200 BCE, was the first important cultural and religious movement in the Andes highlands. The Lanzón was built around 500 BCE during the Early Horizon era of Andean art and received its title from the word for “lance” in Spanish – a reference to the sculpture’s design. The name is misleading because its shape is more akin to a highlands plow, a tool that was employed for agricultural purposes at that period. As a result, it is assumed that the god shown is associated with agrarian worship practices. The Lanzón lies in the center of Chavín de Huantar.

This location was at the time on one of the few passages connecting the steep part of the coast to the impenetrable Amazon. These channels must have been used because of the challenging nature of the landscape. The exposure of Chavín artwork to other civilizations happened due to its geographic position. Archaeologists have discovered textiles that imitate Chavin’s sculptural objects and architecture buried as far south as Karwa, indicating that its influence extended far further than many other cities of the period. The Lanzón represents a fundamental element of Chavín art: the depiction of the jaguar. These portrayals vary from realistic to stylized anthropomorphism, this specific stela coming into the latter group.

The jaguar appears so often in Chavn artworks that it has been proposed that they were the originators of the jaguar religion, worshiping the magical properties and attributes of these felines.

Gate of the Sun (400 CE) in Tiwanaku, Bolivia

| Date Made | 400 CE |

| Civilization | Tiwanaku |

| Type | Stone arch |

| Medium | Andesite stone |

| Location | Tiwanaku, Bolivia |

The Gate of the Sun is an ancient arch made of stone located at Bolivia’s Tiwanaku archaeological site. It is regarded as one of the most significant and fascinating specimens of pre-Columbian Andean art. It is constructed from a single piece of Andesite stone that weighs more than 10 tons. It is beautifully carved with animals, human figures, and geometric patterns, among other themes and symbols. The primary image on the gate is generally understood to represent the sun god, accompanied by other deities and fertility and power symbols. The Tiwanaku civilization’s iconography in Bolivia was influential across the Andean area. The images seen on the gateway can be seen in other regions and linked to contemporaneous or later cultures such as the Inca and Wari.

Other than the traditional fiber recording devices known as quipus, the Andean cultures never left any written traces of their belief systems or religions. However, despite this, academics have been able to acquire knowledge from the Spanish who studied the Incas after the empire’s conquest. The Incas had experienced memorizers who were in charge of transmitting their history through oral traditions, which the Spanish historians documented. Worship of deities representing elements associated with the Earth was a key motif of Andean religions, including the Inca Empire’s religion, particularly for the Inca and Tiwanaku civilizations. In Inca culture, the Sun God was called Inti, and he was represented as a young boy carrying different gold artifacts.

Historians have established parallels between Tiwanaku and Inca images to demonstrate Tiwanaku’s impact on Inca iconography and mythology.

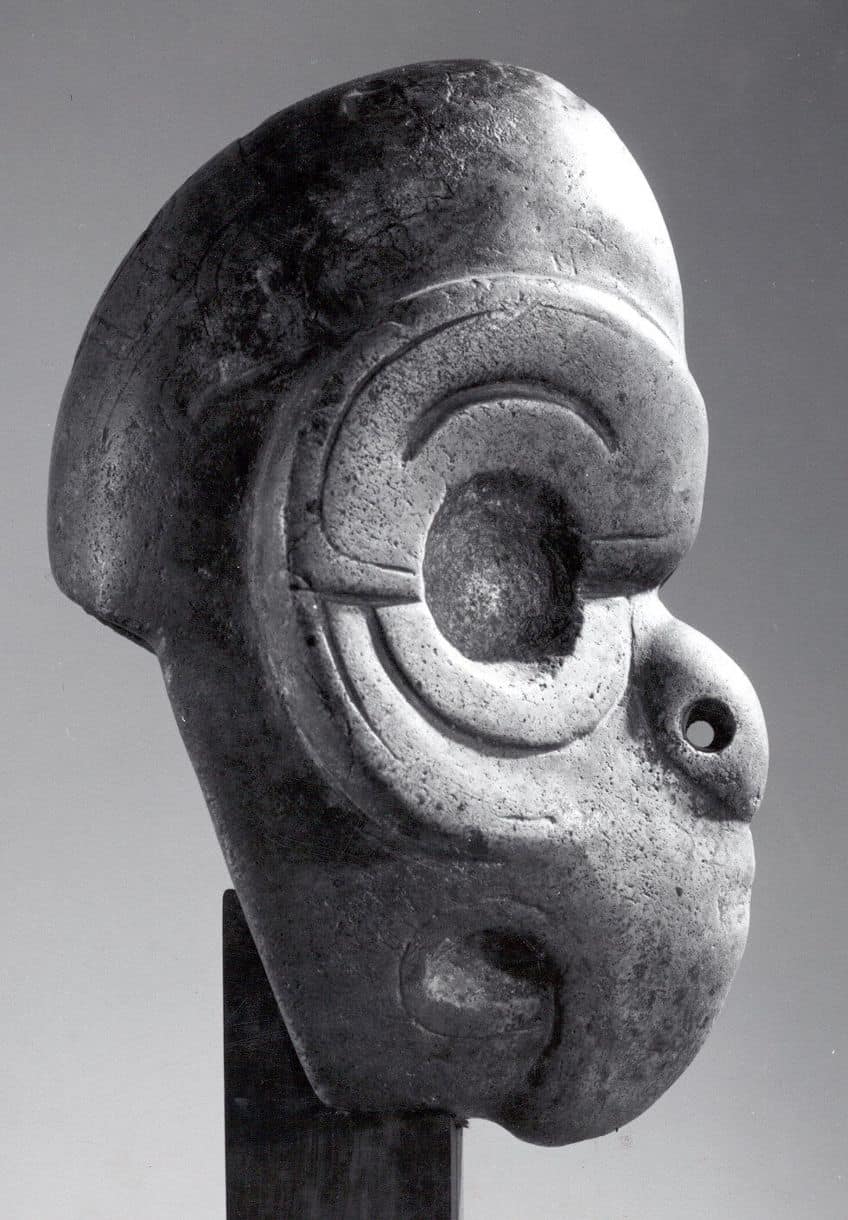

Hatcha Head (c. 7th – 10th Century) in Veracruz, Mexico

| Date Made | c. 7th to 10th century |

| Civilization | Mesoamerican Veracruz |

| Type | Sculpture |

| Medium | Andesite stone |

| Location | Veracruz, Mexico |

Portable carved artworks such as this one from the Classic Veracruz period reproduce in stone the hatchas worn by participants of the traditional Mesoamerican ballgame. This hatcha portrays the head of a warrior or ballplayer wearing a form of jaguar helmet seen in other Mesoamerican regions as a component of a complete jaguar outfit worn by an elite warrior. The depiction, with the wearer’s bottom lip hidden and the jaguar’s tongue extending outwards, blurred the line between the two and can be viewed as a combination of jaguar and man, the human acquisition of the beast’s power. Hatchas are named after the ax-like shape of several of these portable artworks, though their structure and iconography can differ greatly. Those with a more rounded form typically portray animal or human heads. There is a hatcha in the shape of a pair of tied hands in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, which is a rather unusual variation.

Stone versions of these Pre-Columbian artifacts are unlikely to have been donned while actually playing a game that necessitated the players to move fast around the field, occasionally tumbling to the ground to retrieve the ball. There are no visible means to secure the hatcha to the player’s body, and their heaviness would have made them more of an annoyance than an effective kind of protection. These may have been used exclusively during the game’s rituals, or they could have been presented as prizes to be displayed. Hatcha imagery like chained wrists and severed heads might allude to the sort of post-game beheading ceremony seen in El Tajn and other Veracruz locations.

The lifelike representation of tight-fitting headgear in the shape of an animal’s head displayed in this hatcha is nothing like the gigantic feather headdresses used by ballplayers and ceremonial performers in Classic Veracruz and Maya artworks.

Aztec Calendar (c.16th Century) in Mexico City, Mexico

| Date Made | c. 16th century |

| Civilization | Aztec |

| Type | Stone calendar |

| Medium | Basalt |

| Location | National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City, Mexico |

The Aztec Calendar Stone was initially found at Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital city that is now present-day Mexico City. It was buried during the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, only to be rediscovered in 1790. It was eventually relocated to Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology, where it is still on exhibit today. It has grown to become an important symbol of Aztec culture and is universally acknowledged as a Pre-Columbian artifact masterpiece. The calendar stone displays various Aztec mythological and cosmological themes, notably the sun deity, which is depicted by a visage in the stone’s center.

The god is surrounded by four square panels, each with a distinct date sign corresponding to a distinct era in the history of the Aztecs. The stone’s outermost ring comprises symbols reflecting the Aztec calendar’s days and months. There are no evident indicators concerning the authorship or function of the stone, while there are references to the Aztecs building a massive block of stone in their final period of grandeur. The source rock from which it was obtained is from the Xitle volcano and might have come from San Angel. Following the Spanish conquest, it was moved to the Templo Mayor, where it would remain outside, uncovered for many years, with the relief of the stone facing upwards.

Pre-Columbian artwork serves as crucial documentation of the history of the Americas before Europeans arrived. Pre-Columbian art reveals important insights into the ideas, customs, and worldviews of ancient America’s civilizations. It enables us to appreciate how individuals in these civilizations expressed themselves through Pre-Columbian art, as well as to admire the variety and richness of their cultural legacy. Numerous Pre-Columbian artifacts and artistic creations have been destroyed or lost over the centuries, and documenting them helps us to preserve their legacy and cultural relevance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is Understanding Pre-Columbian Art Important?

Beauty, technical mastery, and innovation characterize Pre-Columbian art. Numerous Pre-Columbian artifacts are masterpieces of painting, sculpture, and Pre-Columbian ceramics, and they reflect some of the ancient world’s most outstanding artistic achievements. Due to the impact of the Spanish conquests, it has become essential that we document the works of those civilizations that disappeared in order to document their history and stories for future generations of America’s original inhabitants.

What Characterizes Pre-Columbian Art?

Pre-Columbian artwork is typically very symbolic and full of significance. Numerous symbols and themes in Pre-Columbian art were intimately connected to their various cultural and religious beliefs, and were often utilized to express certain messages and concepts. Pre-Columbian art differed greatly according to the place and culture in which it was developed. For instance, the Maya civilization’s art in Mesoamerica was usually elaborate and intricate, but the Inca empire’s artwork in South America was typified by striking geometric forms.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pre-Columbian Art – The History of Pre-Columbian Artifacts.” Art in Context. May 26, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/pre-columbian-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 26 May). Pre-Columbian Art – The History of Pre-Columbian Artifacts. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pre-columbian-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pre-Columbian Art – The History of Pre-Columbian Artifacts.” Art in Context, May 26, 2023. https://artincontext.org/pre-columbian-art/.

This is an incredible article! If you’re in the market for genuine pre-Columbian artifacts, I can’t recommend Galeria Contici in the U.S. enough. They’ve exceeded all of my expectations!