What Is Verse in Poetry? – Discussing the Structure of Poems

What is verse in poetry? This is what we will discuss over the course of this article. We will examine the differences between stanzas and verses, some of the different types of verses, and a number of examples of poetic verses. If this is something that is of interest to you, keep reading to learn a little more about verse in poetry!

What Is Verse in Poetry?

There is a fundamental issue when it comes to the question of: “What is verse in poetry?”. The reason that there is such an issue is because of the problem of stanza vs. verse. In ordinary communication, we do not generally use the term “verse” when it comes to poetry and we instead use the term “stanza”, but this will be discussed in more detail below.

Once that fundamental issue is no longer a concern, we can instead look at what “verse” does actually mean when not conflated with the term “stanza”. A verse is technically a little broader than a stanza because it can refer to a single line, a whole stanza, or even a poem itself. The reason for this is because a “verse” refers to a section of a poem and the way in which it can be broken up into different parts. That is what we will explore over the course of this article.

Stanza vs. Verse: The Similarities and Differences

Before we examine poetic verse and different types of verses, it would be best to focus on the issue of stanza vs. verse because these two terms are often conflated with one another. Let’s first examine the more commonly-used expression: stanza. This term is used throughout poetic discourse because it has come to simply mean the grouping of lines that are usually separated from other groups of lines through the use of a blank line.

A stanza can, very basically, be termed something akin to a paragraph in prose writing. It is often a unit in which to present aspects of the poem before transitioning to the next. However, where paragraphs in prose writing are usually a means of exploring a single idea before moving on, the same is not necessarily the case in poetry.

While a stanza could make use of a single idea that is explored, many poems will simply use stanzas as part of the whole or, in more contemporary poetry, as something to intentionally distort.

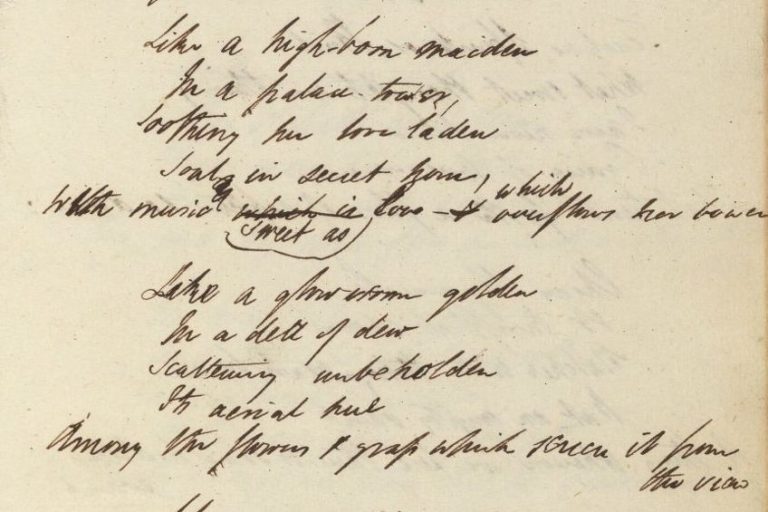

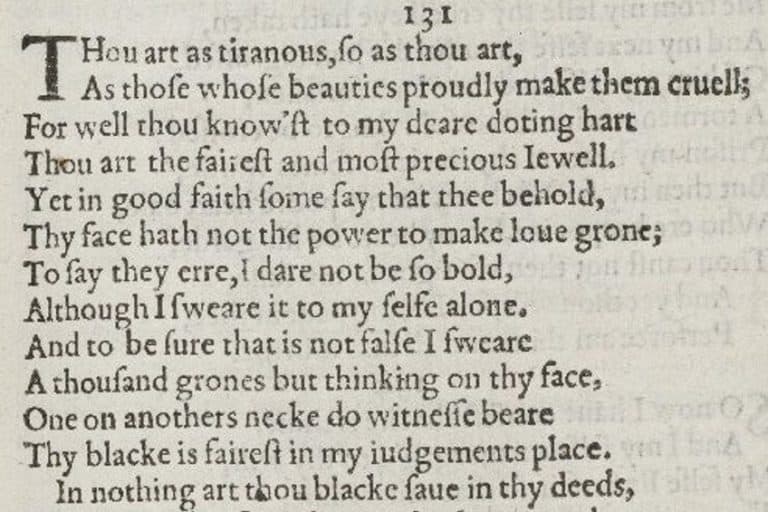

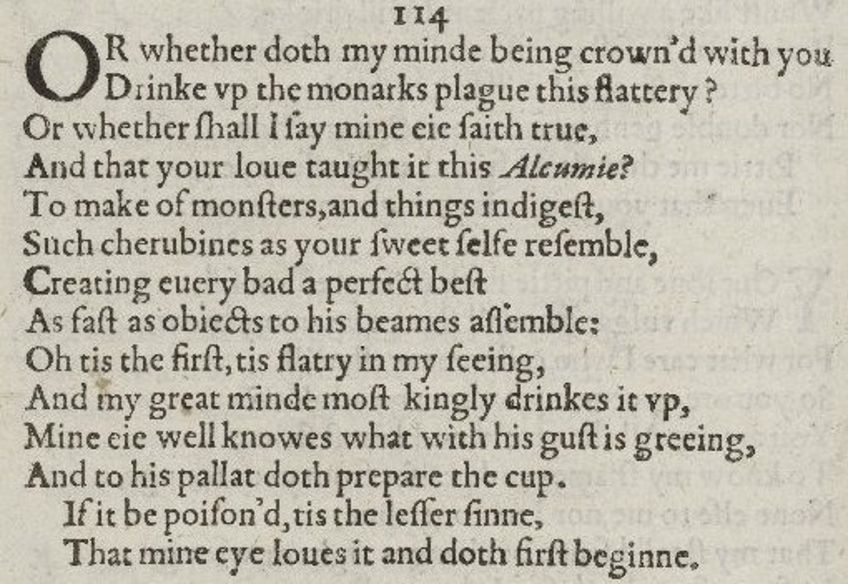

However, stanzas are often associated with rhyming blocks. Take something like a Shakespearean sonnet. They make use of an ABAB CDCD EFEF GG rhyme scheme, and while many sonnets that make use of this particular rhyme scheme will present their sonnet as a single block of text, it could also be separated into three quatrain stanzas and a final two-line stanza in keeping with the rhyme scheme of the poem.

This is not the case with verse. Or at least, this is not necessarily the case with verse. A poetic verse is simply a term used to refer to lines in a poem. It usually refers to lines that are presented in clustered groups (otherwise known as being inside stanzas) or they could be single lines on their own.

It is also generally believed that a “verse” refers to the meter of a poem, and a verse is one that makes use of meter. This can be seen in those forms of verse that do not make use of ordinary structure, such as free verse poetry. This type intentionally eschews the ordinary means of presenting poetic lines with a specific and identifiable metrical rhythm.

Verse as a Synonym for Stanza: Common Uses of Language

The whole issue of “stanza vs. verse” is a significant one as it entails the issue of common usage over technical meaning. There are a pair of linguistic concepts known as prescriptive and descriptive linguistics. The former of these two refers to the way in which some claim that there is a “correct” way to use language. These are the types who will insist that rules of concord or spelling must always be followed.

Prescriptive linguistics is what we are taught in school. It is the supposedly correct way to speak and write, but it stands in opposition to descriptive linguistics. The reality of language, which many prescriptivists do not much like to acknowledge, is that language is constantly changing and evolving. Language does not remain as it is today. For instance, we do not speak like they did during the time of William Shakespeare.

Furthermore, when looking at the history of a language, such as English, its origins tend to be rooted elsewhere. English originated as a Germanic language in the 500s before blending with Frankish (or French) during the early-1000s. By the time we reached the 1500s, modern English had finally arisen. This is why it’s possible for us to read Shakespeare but not something from 500 years before.

This is a view towards descriptive linguistics. This is the way in which we may rather describe language than trying to prescribe rules onto it. It is looking at the way that language is rather than how we want it to be, and so if we stop using a term, it is a natural part of the evolution of language rather than a defiance of the supposed rules of language.

This is worth bringing up because a term like “verse” may be an actual term that could be prescriptively argued to still be in use, but as it has been replaced by “stanza” in common usage, it could be descriptively argued to have lost much of its initial status and meaning.

It is for this reason that “verse” is still found in a number of different places, and in poetry it can be used in a number of different types of verses, but in ordinary speech, it has likely been usurped by “stanza”.

Types of Verses: The Three Main Forms

When it comes to types of verses, it should be understood that while the term “stanza” has practically replaced the term “verse” as a standalone term, the idea of poetic verse does still persist. The term is generally combined with other terms to allow a derived meaning. For this reason, there are three main types of verses that can be adopted. So, let’s take a look at each of them.

Rhymed Verse

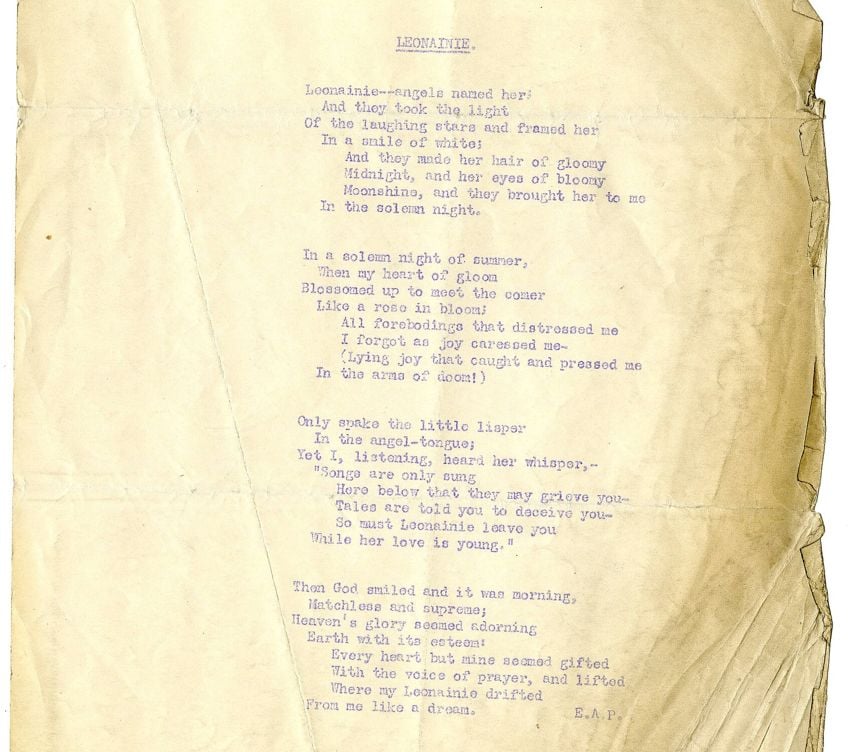

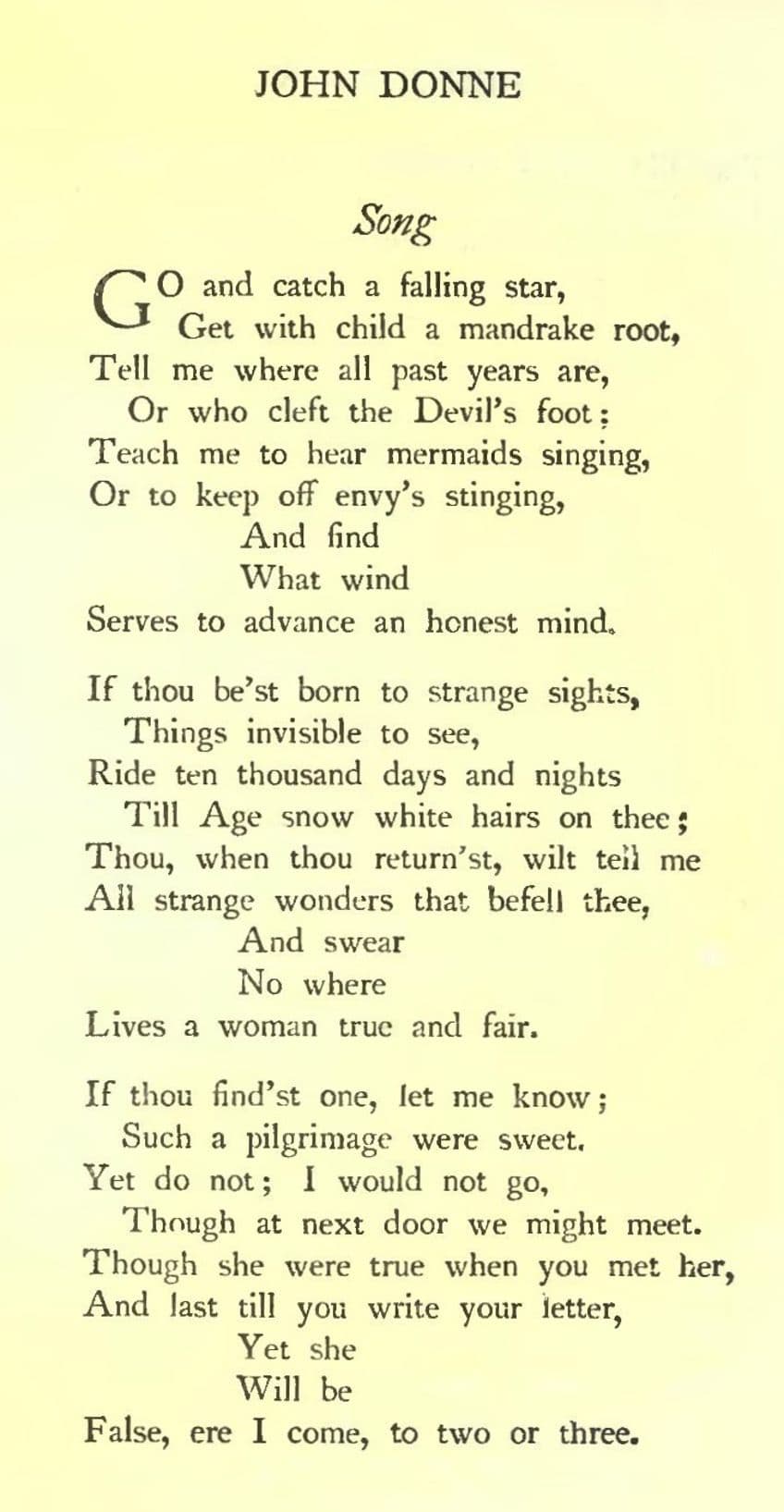

This simply refers to any kind of a poem that makes use of rhyme. This does not mean that there is a specific rhyme, but simply that it does use rhyme in some or another sense. Common types of rhymed verse include traditional forms of sonnets and limericks. Rhymed verse can also make use of meter, but this is not a necessary part of this particular example of verse.

However, traditional rhymed verse usually used meter too.

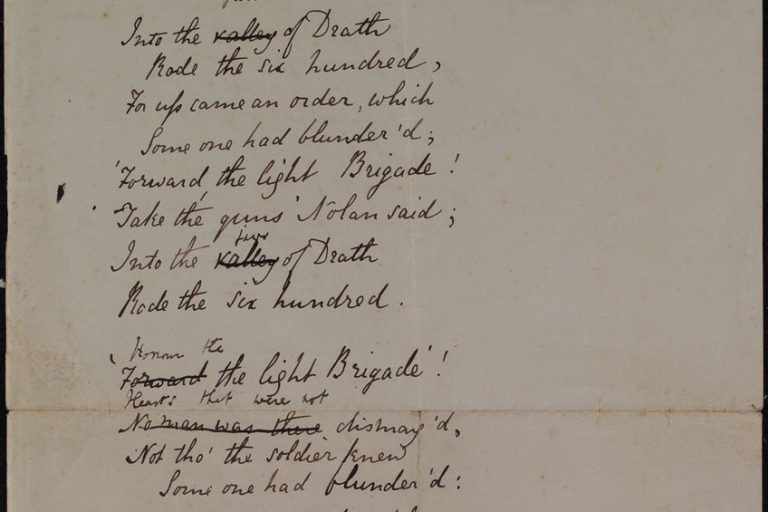

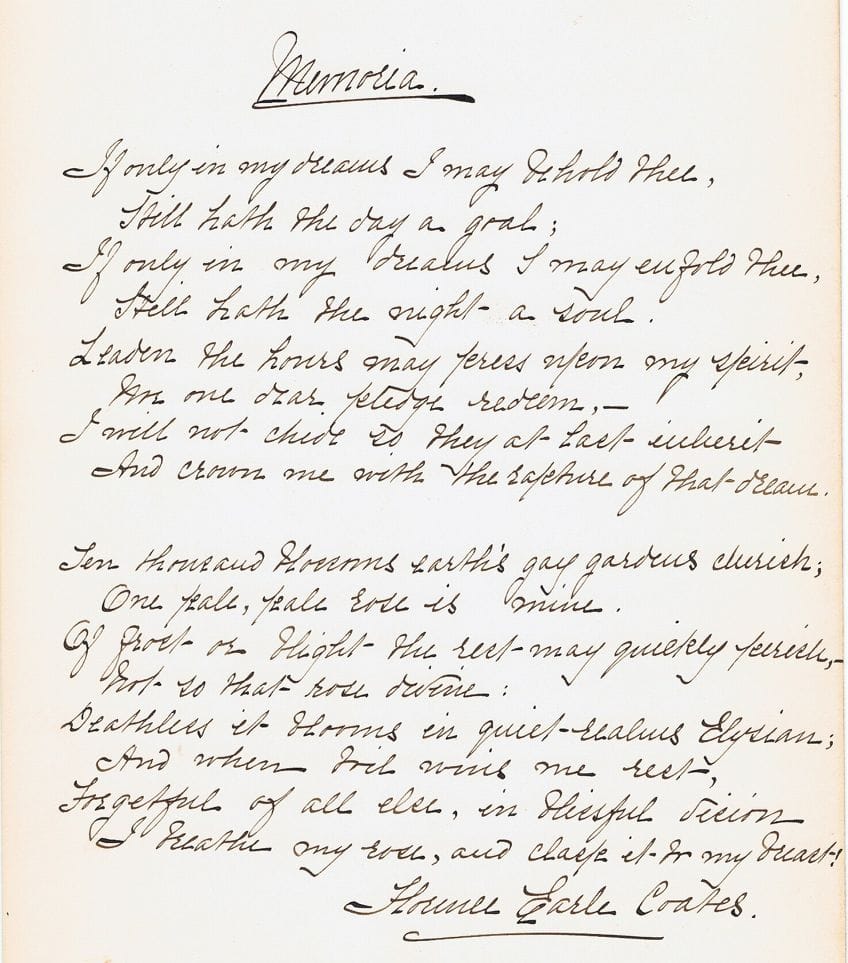

Blank Verse

This term is not as well-known as free verse, but it refers to a kind of unrhymed poetic verse that still makes use of meter. This means that it uses a strict example of meter but does not conform to the kind of rhyme schemes that you might ordinarily find in a lot of poetry.

Free Verse

This example of verse is perhaps the most famous in the contemporary age as it refers to a poem that does not make use of a sustained rhyme scheme or meter. This has become a common example of verse in modern poetry.

It has become prominent because of its denial of traditional poetic elements.

Examples of Poetic Verse

As has been mentioned, the term “verse” is often conjoined with a different term to refer to a specific type of poetry. Namely, rhymed verse, blank verse, and free verse. We will examine two of these different examples of verse below. The use of a specific type of verse in a poem is a common occurrence, and so there are many examples other than these two that have been used.

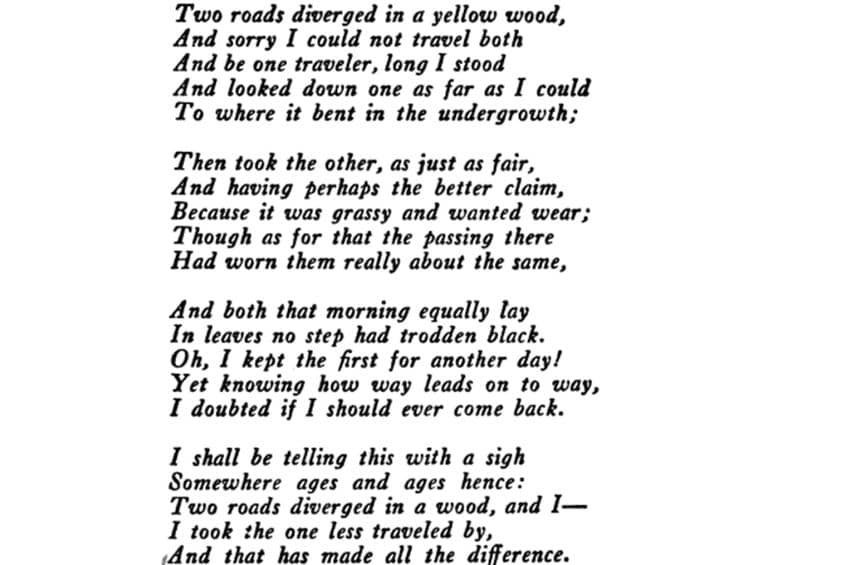

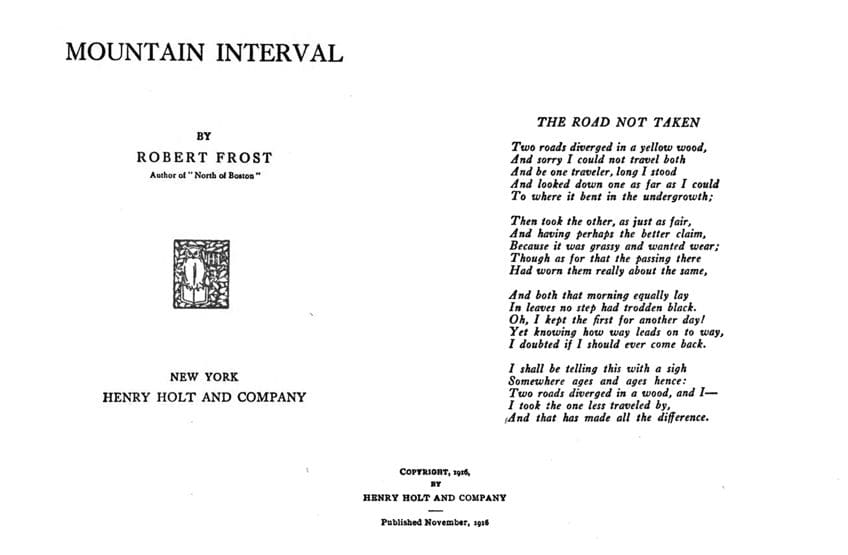

The Road Not Taken (1915) by Robert Frost

| Date Published | 1915 |

| Type of Poem | Narrative poem |

| Rhyme Scheme | ABAAB |

| Meter | Iambic tetrameter |

| Topic | Life choices |

When we use the term “verse” in poetry, we often think of free verse and blank verse, but rhymed verse is equally as usable. The term itself is not as common as there are usually a number of other examples of specific types of rhymed verse, such as sonnets.

However, this poem by Robert Frost is a good example of rhymed verse poetry.

This poem makes use of an ABAAB rhyme scheme, but it also makes use of a particular meter. This is another aspect of verse that is often considered to be integral to the idea. In this poem, the metrical verse style that is adopted is iambic tetrameter, and this entails the use of four metrical syllables within each line in which each metrical unit entails two syllables, one stressed and one unstressed.

The Waste Land (1922) by T.S. Eliot

| Date Published | 1922 |

| Type of Poem | Free verse epic poem |

| Rhyme Scheme | Variable |

| Meter | Variable |

| Topic | Post-WW1 disillusionment |

When it comes to the more derivative meaning of “verse” as something fundamentally attached to a separate term, it can be used to describe a poem such as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. This particular poem makes use of a number of different metrical structures throughout its duration, and this means that it is an example of a free verse poem. Free verse poetry entails the lack of ordinary poetic rules that tend to control certain examples of poetry.

This poem does not have a specific rhyme scheme or meter, and it instead fluctuates between different structures over the course of the poem. Instead of relying on ordinary poetic forms, this poem makes use of a number of other poetic techniques to ensure that it has the kind of unity that would usually come with rigidly adhering to a poem type that has a built-in rhyme scheme.

And with that final point, we come to the end of our look at the question: “What is verse in poetry?”. We have examined some of the issues inherent in this term, such as the way in which it can be compared to the term “stanza”, but we also discussed some of the different types of verses and an example of verse types in two separate poems. Hopefully, this has given you a good overview of the idea of verse in poetry!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Verse in Poetry?

A verse is simply a part of a poem. This could mean that the term refers to a single line or a whole stanza. In fact, the term can even be used to refer to an entire poem. However, the term is often used in a more interchangeable capacity with the term stanza. Ultimately, a verse is generally understood as a single or a number of lines in some kind of a sequence.

What Is the Difference Between a Verse and a Stanza?

These two terms are often seen as synonyms of one another. However, a verse can refer to a single line, generally of metrical composition, while a stanza always refers to a group of lines that are generally separated from one another with a blank line. This technical distinction does not stop most from simply referring to them as stanzas instead of as verses.

What Is the Common Usage of the Stanza vs. Verse?

In terms of common usage, the term stanza has largely replaced the word verse outside of a specific example of verse structures, such as free verse or blank verse poetry. Today, this means that a verse is usually used in a derivative sense, while a stanza has come to mean the lines of a poem that are separated by a blank line. However, the term verse is also commonly used to refer to the equivalent of a stanza in musical lyrics.

What Is the Most Famous Verse in a Poem?

There are many immensely famous verses, but perhaps the most famous example of verse in the English language is the first line of the Shakespearean poem, Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? This first line has become one of the most famous in all of English poetry, and as a standalone line, it is one of the most prominent of them all.

How Long Can a Verse in a Poem Be?

There is no set length for a poetic verse. A verse could be a single line, or it could be comprised of multiple lines that make up a stanza. Additionally, there is no hard rule for the length of individual lines in a poem, and so if one were to take a verse as a single line, there are no definitive and enforceable length requirements.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “What Is Verse in Poetry? – Discussing the Structure of Poems.” Art in Context. September 11, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-is-verse-in-poetry/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 11 September). What Is Verse in Poetry? – Discussing the Structure of Poems. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-is-verse-in-poetry/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “What Is Verse in Poetry? – Discussing the Structure of Poems.” Art in Context, September 11, 2023. https://artincontext.org/what-is-verse-in-poetry/.