Mask of Tutankhamun – See the Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was just nine years old when he was crowned King of Egypt during the New Kingdom’s 18th dynasty. His tale might have been erased from history if Howard Carter, an archeologist, had not discovered his tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. His highly preserved tomb included a plethora of artifacts that provide us with valuable insight into this time of Egyptian history, such as the funerary mask of Tutankhamun.

Table of Contents

The Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun

| Artist | Unknown |

| Material | Gold, carnelian, lapis lazuli, obsidian, turquoise, and glass paste |

| Date Created | c. 1323 BCE |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt |

The gold funerary mask of Tutankhamun was created for the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt pharaoh. It is one of the world’s most well-known works of art and a significant emblem of ancient Egypt. The funerary mask of Tutankhamun is 54 cm tall, weighs almost 10 kilograms, and is adorned with semi-precious stones in the image of the Egyptian deity of the afterlife, Osiris. An ancient Book of the Dead spell is inscribed in hieroglyphs on the mask’s shoulders.

In 2015, the mask’s 2.5-kilogram plaited beard came off and was swiftly put back on by museum staff. The mask is “not just the archetypal artwork from Tutankhamun’s tomb, but it is possibly the best-known relic from ancient Egypt itself”, according to Nicholas Reeves, an Egyptologist. Some Egyptologists have speculated since 2001 that it was initially meant for Queen Neferneferuaten.

Who Was Tutankhamun?

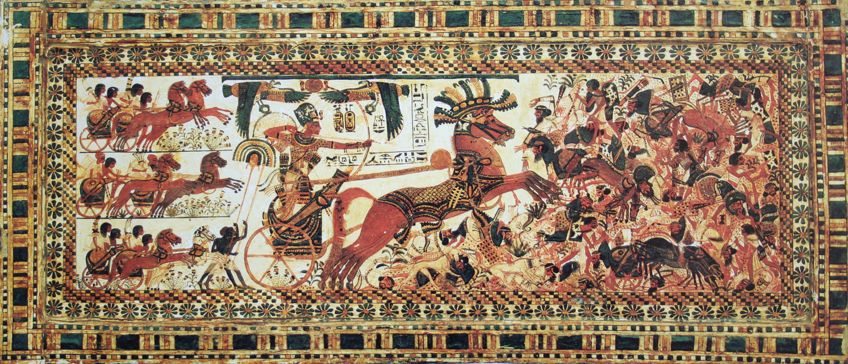

Tutankhamun ruled following the Amarna period, when Tutankhamun’s presumed father, Pharaoh Akhenaten, shifted the kingdom’s religious focus to the deity Aten, the sun disc. Akhenaten relocated his capital to Amarna in Middle Egypt, far away from the former pharaoh’s capital. Tutankhamun transferred the emphasis of the country’s devotion back to the deity and restored the religious seat to Thebes after Akhenaten’s passing and the tenure of a short-lived pharaoh, Smenkhkare.

If you hope to complete craft

projects where you need paint that will work well for any number of surfaces, then craft paint is your

go-to! The consistency is smooth, creamy, and easy to use.

Tutankhamun died at the age of 18, prompting numerous experts to hypothesize on his cause of death – murder by a strike to the skull, a chariot accident, or even a hippopotamus attack! The truth is still a mystery. Tutankhamun’s considerably older advisor, Ay, wedded the widowed Ankhesenamun and ascended to the throne. His premature demise had effectively wiped his presence from Egyptian memory, which is most likely why his tomb had not been robbed like every other.

The magnificent riches of the tomb make us wonder: what did genuinely great monarchs, such as Ramesses, have buried with them? Tutankhamun is said to have died before his tomb was properly constructed, and his replacement had him buried quickly in a humble tomb intended for someone else.

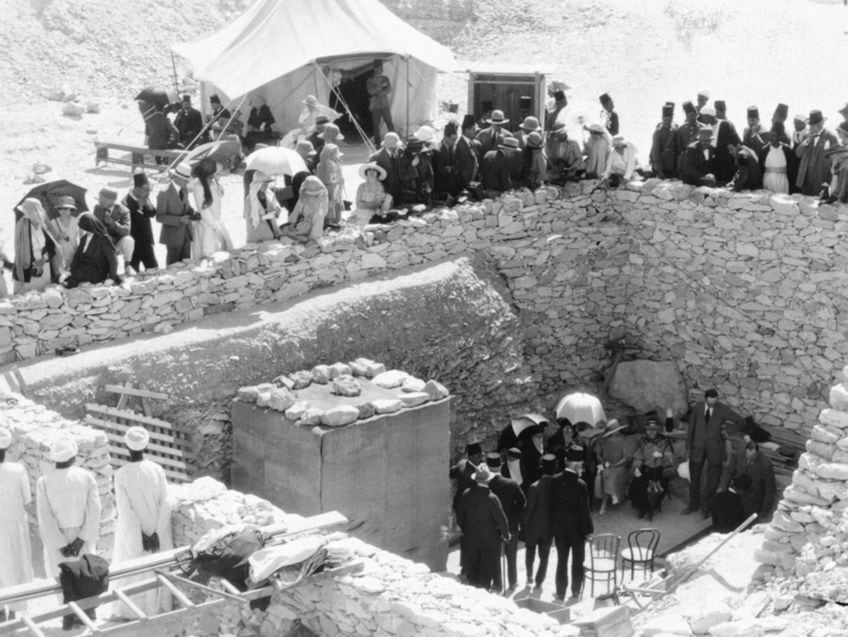

Discovery of the Tomb

Howard Carter, a British Egyptologist, dug for several years in the Valley of the Kings, a royal burial cemetery situated on the western bank of the Thebes, an ancient city, in the early 20th century. He was about to run out of funding to continue his archaeological excavation when he begged his sponsor, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, for financing for one more season. Lord Carnarvon extended his stay for another year, and what a year it would turn out to be. Carter discovered the first of 12 stairs leading to Tutankhamun’s tomb at the start of November 1922.

He swiftly found the stairs and dispatched a telegraph to Carnarvon in England so that they might jointly unveil the tomb.

Carnarvon promptly left for Egypt, and on the 26th of November, 1922, they drilled a hole in the antechamber’s door to peer inside. The heated air leaving the chamber caused the candle flame to waver at first, but as his eyes became used to the brightness, features of the place inside appeared slowly from the mist, sculptures, weird animals, and gold – everywhere the gleam of gold.

Howard Carter explained: “The sealed door was before us, and with its removal, we were to erase the centuries and be in the company of a monarch who ruled around 3,000 years ago. My emotions were a bizarre combination as I climbed the podium, and I dealt the first blow with a shaky hand. A breathtaking sight unveiled what appeared to be a complete wall of gold”. The golden Great Shrine was what they saw. They hadn’t yet arrived at the pharaoh’s burial chamber. They couldn’t fathom their good fortune in uncovering what is now thought to be the sole pharaoh’s tomb that had remained complete and unspoiled for centuries.

Naturally, in that modern age of radio and press news, the finding caused quite a stir. Egyptomania took over the world, and everything was named after Tutankhamun. The tomb’s unearthing sparked a surge of renewed interest in ancient Egypt. Even today, the famed wealth and richness of the tomb, as well as the thrill of the discovery, astound us. We may be so taken with the overwhelming quantity of valuable material that we fail to recognize how wonderful the pieces from within the tomb are as artworks. The crew faced a massive challenge in categorizing the items. Carter spent 10 years meticulously cataloging and photographing the items.

Tutankhamun’s Innermost Coffin

Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus housed not one, but three coffins containing the king’s body. The two exterior coffins were fashioned of wood, covered in gold, and embellished with turquoise and lapis lazuli among other semiprecious stones. The inner casket was composed of solid gold. This coffin was not the glittering golden figure that we currently see in the Egyptian Museum when Howard Carter first found it. According to Carter’s excavation reports, it was coated with a thick black pitch-like substance that reached from the hands all the way to the ankles.

Evidently, throughout the burial procedure, the casket had been generously anointed with this substance.

The gods were considered to have silver bones, golden skin, and hair that had been fashioned from lapis lazuli, thus the monarch is depicted here in his nether worldly representation in the afterlife. He wields the flail and crook, which represent the king’s authority to reign. Adorned with semi-precious stones, the goddesses Wadjet and Nekhbet extend their wings across his body. Two other goddesses, Nephthys and Isis, are engraved onto the golden lid underneath these two.

The Mask of Tutankhamun

It’s made of two layers of high-karat gold. According to X-ray crystallography performed in 2007, the mask is principally constructed of copper-alloyed 23-carat gold to assist the cold work needed to sculpt the mask. The mask’s surface is coated in a very thin coating of two distinct gold alloys: a lighter 18.4 karat gold for the neck and face, and a 22.5 karat gold for the remainder of the funerary mask. The face depicts the pharaoh’s typical representation, and excavators discovered the identical image everywhere throughout the tomb, particularly in the guardian sculptures. He bears a headcloth with the royal emblem of a vulture and a cobra, representing Tutankhamun’s sovereignty over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

In practically all remaining ancient Egyptian artworks, the ears are pierced for earrings, a characteristic that was believed to have been intended for queens and children. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass said that the “ear piercing notion is incorrect because all 18th Dynasty monarchs wore earrings during their reign”. The funerary mask of Tutankhamun is inlaid with gemstones and colored glass, comprising quartz for the eyes, lapis lazuli for around the eyes and brows, obsidian for the pupils, amazonite, carnelian, turquoise, and faience.

The 2.5-kilogram slender gold beard, inset with blue glass for a plaited appearance, had been detached from the funerary mask when it was discovered in 1925, but it was connected to the chin utilizing a wooden dowel in 1944.

When the funerary mask of Tutankhamun was taken out of its display cabinet for cleanup in August 2014, the beard came off. In an effort to repair it, the museum staff employed quick-drying epoxy, which caused the beard to be off-center. The damage was discovered in January 2015 and restored by a German group who repaired it with beeswax, a natural substance employed by the ancient Egyptians. Eight Egyptian Museum staff were reprimanded and disciplined in January 2016 for reportedly neglecting professional and scientific repair processes and creating lasting damage to the funerary mask. Those facing punishment included a former restoration director and a former museum director.

Inscription on the Mask

On the shoulders and back, two horizontal and 10 vertical lines of Egyptian hieroglyphs form a protection spell. This spell originally featured on masks 500 years earlier than Tutankhamun’s reign and was referenced in Chapter 151 of the Book of the Dead. When translated it says:

“The night bark of the sun-god is thy right eye, the day bark is thy left eye, thy brows correspond to the Ennead of the Gods, thy forehead represents Anubis, thy neck is Horus’s, and thy strands of hair belong to Ptah-Sokar. You are standing in front of Osiris. He gives thanks to thee; thou guide him in the right path, thou smite Seth, so that he may destroy thy foes before the Ennead of the Gods in the magnificent Castle of the Prince, that exists in Heliopolis. The deceased Osiris, King of Upper Egypt Nebkheperure, was resurrected by Re.”

The Egyptian deity of the afterlife was Osiris. The ancient Egyptians thought that Osiris-like rulers would govern the Realm of the Dead. It never completely superseded the previous sun worship, which held that deceased rulers were resurrected as the sun-god Re, whose flesh was formed of lapis lazuli and gold. This fusion of ancient and modern faiths resulted in a mingling of symbols within Tutankhamun’s coffin and tomb.

Probable Reuse and Alterations

Several artifacts in Tutankhamun’s tomb are assumed to have been altered for Tutankhamun’s usage after being constructed for one of the two pharaohs who reigned briefly before him: Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkare. According to Egyptologists, the funerary mask of Tutankhamun was one of these items. They claim that the pierced ears imply that it was made for a female emperor, which Neferneferuaten was; that the slightly distinct composition of the foundational alloy indicates that it was created independently of the remainder of the mask; and that the cartouches on the mask exhibit indications of being changed from Neferneferuaten to Tutankhamun.

The headcloth, ears, and collar of the mask were produced for Neferneferuaten, but the face, which was fashioned as an independent piece of metal and fits earlier depictions of Tutankhamun, was later added, replacing an initial face that apparently represented Neferneferuaten. Nevertheless, the metal conservation specialist who restored the mask in 2015, Christian Eckmann, said there are no indications that the face is made of a different gold than the remainder of the funerary mask or that the cartouches have been changed.

Purpose of the Mask and Tomb

This is one of the finest pieces of Egyptian art, and it was nearest to the king’s mummified body. It’s iconic and loaded with meaning. It was an elevated item with a purpose: to assure the king’s resurrection. Egypt’s funeral art served a function other than remembering deceased loved ones. Art played a part in their religion, in the philosophy that backed royalty, and in cementing society’s hierarchy. Such elaborate burial traditions may indicate that the Egyptians were obsessed with death.

Due to their enormous love of life, they started to make provisions for their passing early on.

They couldn’t think of any finer life than the one they were living, and they wanted to ensure that it would remain after death. But why keep the body? The Egyptians thought that the mummified remains housed the soul. If the body perishes, the spirit may perish too. The notion of a “spirit” was complex, including three spirits. The ka, was seen as a “duplicate” of the person, and would therefore stay in the tomb and would necessitate sacrifices. The ba, or “spirit”, was able to leave and make its way to the grave. Finally, it was the akh, which may be viewed as the “soul”, who had to go through the Netherworld to the Final Judgment and entry into the Afterlife. All three were crucial to the Egyptians.

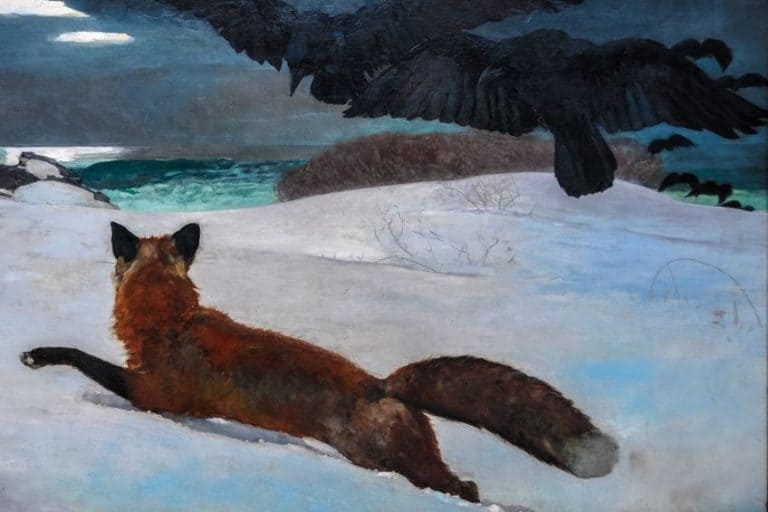

Anthropomorphic masks have frequently been utilized in ceremonies related to the deceased and leaving spirits in societies where burial practices are prominent. Funerary masks were regularly worn to conceal the deceased’s face. In general, their objective was to portray the deceased’s characteristics, both to honor them and to create a link with the spiritual realm through the mask. They were sometimes used to compel the spirit of the recently deceased to depart for the spirit realm. Masks were also created to keep harmful spirits away from the departed.

The ancient Egyptians put stylized masks with generalized characteristics on the faces of their deceased in the Middle Kingdom until the 1st century CE. The funeral mask guided the deceased’s spirit back to its ultimate place of rest in the body. These masks were often fashioned of fabric coated with plaster or stucco and then painted. Gold and silver were utilized by more prominent people. The funeral portrait mask constructed about 1350 BCE for Pharaoh Tutankhamun is one of the most magnificent specimens. Broken gold portrait masks were discovered in Mycenaean graves about 1400 BCE. Gold masks were also put on the faces of Cambodian and Thai rulers who had died.

The funerary mask of Tutankhamun was made for the pharaoh, Tutankhamun, the Egyptian Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty who ruled approximately 1323 BCE. Howard Carter unearthed it in 1925, and it is presently kept at Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. This funerary mask is one of the world’s most famous art objects. The tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun was first discovered in 1922 in the location of the Valley of the Kings and opened after three years. The excavation crew, directed by Howard Carter, an English archaeologist, would have to wait another two years before they could uncover the huge sarcophagus housing Tutankhamun’s mummy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Tutankhamun?

King Tutankhamun was dubbed the Boy King because he started his rule at the age of nine! Tutankhamun passed when he was just 18 years old, and his body was preserved, as the ancient Egyptians did with their deceased. His golden casket was placed in the Valley of the Kings in a tomb surrounded by 5,000 precious items. A golden throne, a cobra, ceramics, and large trunks were among the valuables. The tomb also included King Tut’s sandals, in addition to a golden burial mask.

Was the Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun Originally Created for the Boy King?

It is believed that a number of the objects in Tutankhamun’s tomb were modified for Tutankhamun’s use after being produced for one of the two pharaohs who served before him, possibly either the pharaoh Smenkhkare or perhaps even Neferneferuaten. One of these artifacts was the burial mask of Tutankhamun. Some Egyptologists claim that the mask’s pierced ears indicate that it was made for a female emperor, such as Neferneferuaten, that the underpinning alloy’s varying content indicates that it was produced independently of the rest of the mask and that the cartouches indicate that Neferneferuaten’s name was subsequently changed to Tutankhamun.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Mask of Tutankhamun – See the Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun.” Art in Context. January 10, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/mask-of-tutankhamun/

Meyer, I. (2023, 10 January). Mask of Tutankhamun – See the Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mask-of-tutankhamun/

Meyer, Isabella. “Mask of Tutankhamun – See the Funerary Mask of Tutankhamun.” Art in Context, January 10, 2023. https://artincontext.org/mask-of-tutankhamun/.